Introduction

Iron, recognized as element 26 in the periodic table, stands as a cornerstone of scientific inquiry. As a versatile transition metal, it underpins numerous industrial and health-related advancements. The diverse Iron applications, particularly in steel production and medical treatments, highlight its significance. By May 2025, its role continues to evolve on a global scale. This article delves into these Iron applications, tracing their roots to ancient metallurgy and exploring their modern manifestations. It also examines Iron discovery by early civilizations and its enduring Iron properties, such as strength and magnetic behavior. Furthermore, the study extends to Iron compounds, which play a vital role in chemical processes.

Abundant in Earth’s crust, iron is predominantly found in minerals like hematite, shaping technological progress. Historical narratives reveal its gradual integration into human society. Ongoing research underscores its potential in sustainable technologies. As a result, iron’s influence spans multiple disciplines. Its development is meticulously documented in scientific literature. This exploration aims to enhance our understanding of element 26 in 2025.

Building on this foundation, iron’s impact reaches beyond traditional uses. Advanced analytical methods, including spectroscopy, refine our knowledge. The element’s contributions remain a focal point of study. Therefore, this article seeks to provide a comprehensive overview. Its relevance in contemporary science is undeniable. Transitioning to its inherent qualities, the next section explores these attributes in detail.

Physical and Chemical Properties of Iron

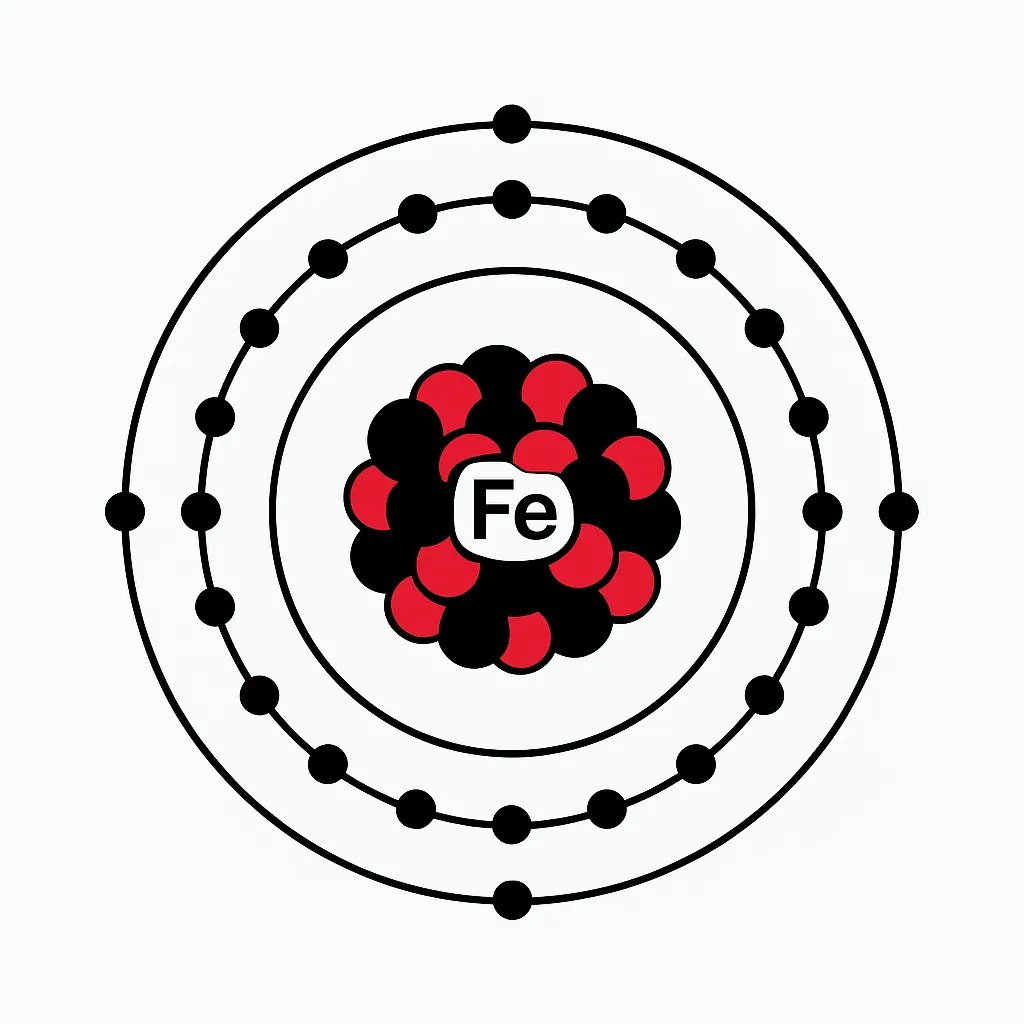

Iron properties establish it as a foundational element, boasting a silvery-gray luster that catches the eye. With an atomic number of 26 and an atomic weight of 55.85, it exhibits remarkable stability, melting at 1,538°C and boiling at 2,862°C. These characteristics, combined with its high tensile strength and ductility, make iron a preferred material in structural applications. Its body-centered cubic structure further enhances mechanical resilience, contributing to its widespread utility.

Moreover, iron’s chemical versatility shines through its oxidation states, ranging from -2 to +6, which support a variety of industrial processes. This adaptability, paired with moderate electrical conductivity, renders it suitable for specialized uses. Although naturally prone to corrosion, iron’s magnetic properties and malleability improve significantly when alloyed. Such traits have cemented its role in engineering and technology.

Transitioning from these inherent qualities, iron’s ability to resist wear when properly treated adds to its value. Its thermal conductivity proves advantageous in high-temperature environments. While brittle in its pure state, alloying transforms it into a robust material. These Iron properties not only drive innovation but also underpin advancements in material science. Consequently, the next section delves into the historical context of its emergence.

The Historical Background of Iron Discovery

Iron discovery transformed human civilization, with evidence of its use dating back to around 1200 BCE. Early societies initially extracted it from meteorites, recognizing its potential. By 1000 BCE, the Middle East had mastered ironworking, ushering in the Iron Age. This period saw the development of smelting techniques, which revolutionized tool production. Iron discovery laid the groundwork for technological progress across continents.

As techniques evolved, the Hittites refined iron production methods by the early centuries. By 500 BCE, iron had spread to Europe and Asia, supported by archaeological findings. This expansion enhanced agricultural efficiency and societal structures. The advent of blast furnaces in the 14th century marked a significant leap forward. Iron discovery thus became a catalyst for industrialization.

Building on this historical progression, modern extraction methods have uncovered new deposits. Regions like Australia and Brazil now supply iron ore globally. Advanced techniques, such as X-ray analysis, improve its study. These developments ensure a steady resource flow for industries. Therefore, the legacy of Iron discovery continues to shape contemporary applications. The following section explores these practical uses in depth.

Applications of Iron in Industry and Technology

Iron applications form the backbone of construction and manufacturing worldwide. Steel, primarily composed of iron, supports skyscrapers, bridges, and infrastructure with remarkable strength. Accounting for nearly 98% of iron’s use, this alloy withstands tension and compression effectively. Automotive industries rely on iron for durable components, enhancing vehicle longevity. Shipbuilding also benefits, as iron’s structural integrity ensures seaworthiness.

Extending beyond traditional sectors, iron plays a crucial role in renewable energy. Wind turbines incorporate iron to harness sustainable power. Additionally, its use in railway systems provides reliable transport networks. The health sector leverages iron in medical instruments and supplements to combat anemia. However, mining iron poses environmental challenges that recycling efforts aim to mitigate.

Transitioning to emerging fields, iron’s presence in electronics grows, particularly in transformers. Its demand surges with infrastructure development projects. Iron applications promote a balance between functionality and ecological responsibility. This versatility positions iron as a key player in modern innovation. Consequently, the next section examines the chemical compounds derived from iron.

Chemical Compounds and Their Significance

Iron compounds reveal the element’s chemical versatility, with iron oxide (Fe₂O₃) standing out as a prime example. Widely utilized as a pigment in paints and a catalyst in industrial reactions, this compound enhances product quality. Ferrous sulfate, another key compound, addresses iron deficiency by supporting human health. These substances form stable complexes, particularly in +2 and +3 oxidation states.

Moreover, iron’s biological role is evident, as hemoglobin relies on it to transport oxygen efficiently. Yet, excessive intake can lead to toxicity, necessitating careful management. The colorful ions of iron, ranging from red to yellow, prove valuable in analytical chemistry. Iron compounds also bolster steelmaking by improving alloy characteristics.

Building on these applications, iron’s compounds contribute to water purification and corrosion-resistant coatings. Their thermal stability suits high-heat industrial settings. Research into nanotechnology explores their potential further. Thus, the study of Iron compounds continues to evolve. Their role in fertilizers and pharmaceuticals is under investigation. This chemical diversity underscores iron’s scientific importance.

Leave a Reply