Section One: Historical Background and Introduction of the Potato to the World

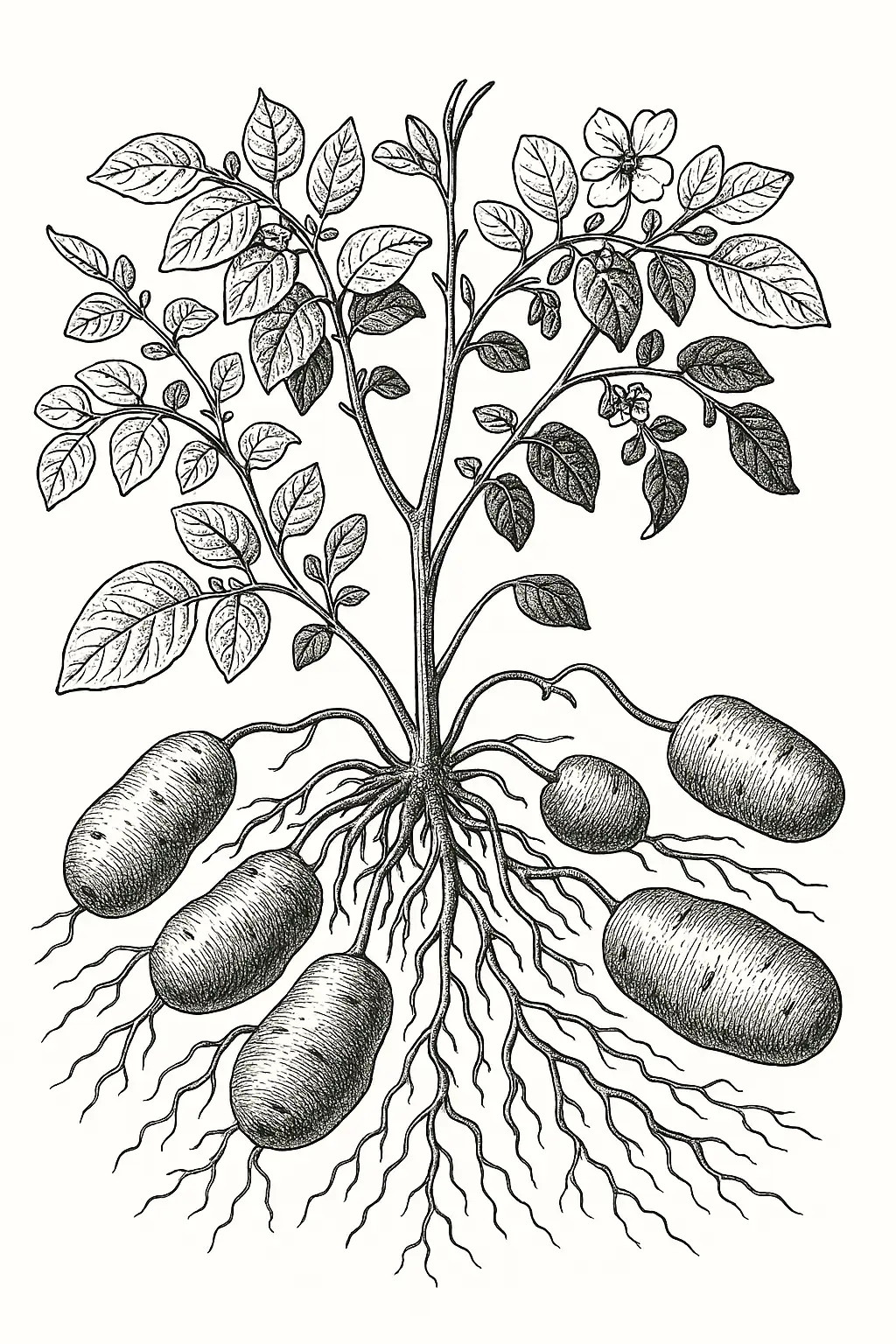

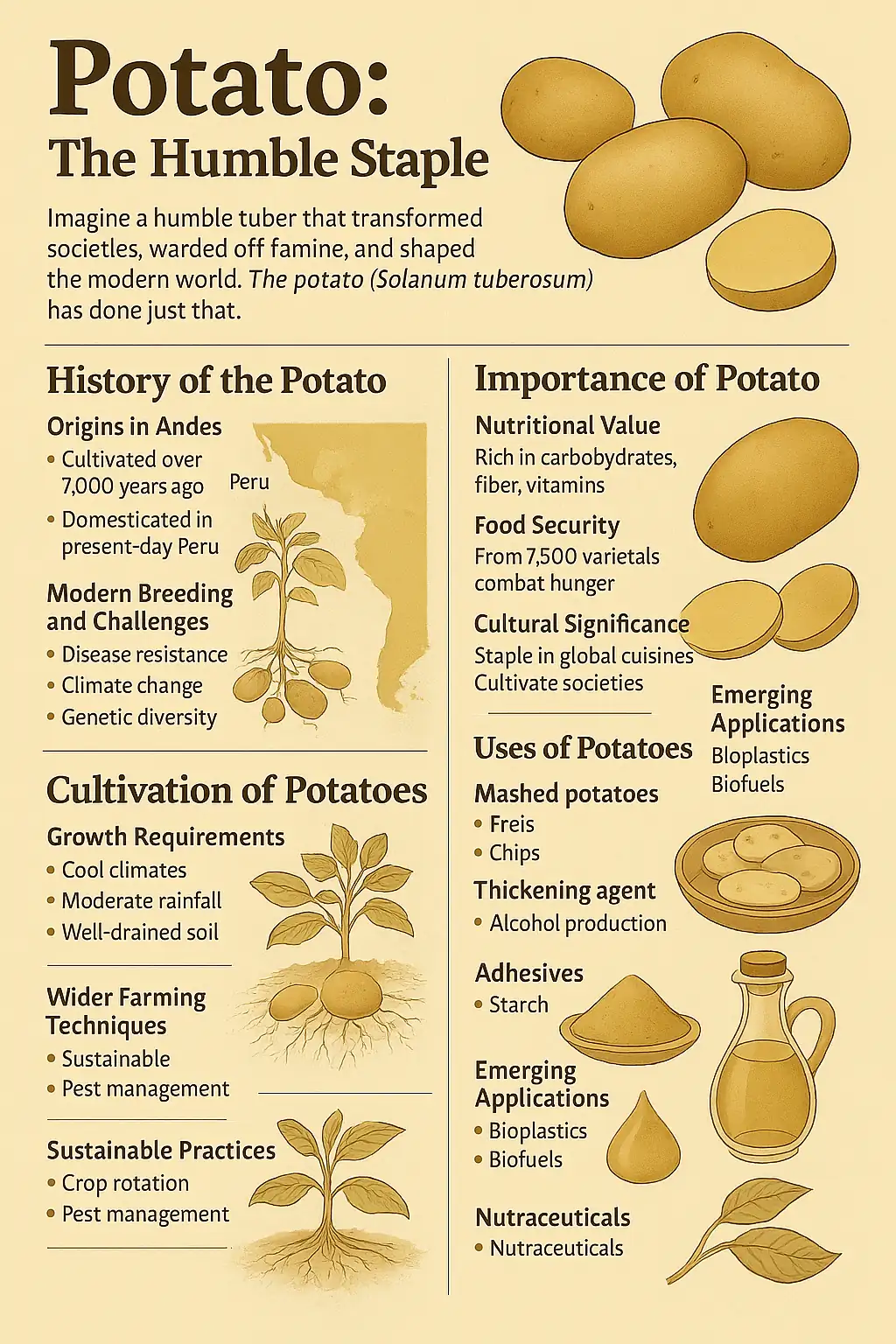

The potato (Solanum tuberosum) is an ancient tuber native to the Andean regions of South America, where human populations in the highlands of Peru and Bolivia have based their livelihood and agriculture on it for over five thousand years. In the early sixteenth century, this plant was brought to Europe by Spanish conquerors. The earliest documented reports indicate that around 1570, the potato was cultivated ornamentally in the royal gardens of Spain and Italy, but it had not yet gained acceptance as a food by the end of the seventeenth century. Factors such as the tuber’s unusual appearance and its classification within the Solanaceae family—which includes some toxic species—fostered initial distrust among Europeans regarding its consumption.

However, in the early eighteenth century, amid successive grain crises, both state authorities and church leaders in Prussia and France gradually recognized the potato’s exceptional yield per unit area and its resilience to cold climates and poor soils. A notable example is Frederick the Great of Prussia, who in the mid-eighteenth century issued the “Potato Day” decree, mandating local estates to establish potato fields. By 1766, over 30,000 hectares of the wind-swept lands surrounding Berlin were dedicated to potato cultivation, an initiative that quickly helped to avert a looming food crisis in the region.

Section Two: The Role of the Potato in the Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Food Revolutions

In the latter half of the eighteenth century, agricultural reforms aimed at diversifying crops and promoting potato cultivation spread across many European countries. In Scotland, Protestant churches and large landowners adopted the crop and allocated potato quotas to their tenant farmers. The direct consequence of this policy was an increase in per‑capita food availability from 1,600 to approximately 2,000 kilocalories per day, reducing famine‑related mortality in rural areas by up to 40 percent.

China provides another example of successful potato introduction in the late nineteenth century. Confronted with recurrent droughts and pests, the Qing government implemented a planned distribution of resistant potato varieties in the mountainous regions of Yan’an and Sichuan. Archival records reveal that between 1876 and 1879, over one million hectares were planted with potatoes, providing an additional 10–15 percent of the daily caloric needs for millions of Chinese citizens and saving them from certain starvation.

In North America, the early nineteenth century coincided with the expansion of the railroad and increased westward migration. Potato seeds were easily loaded onto trains and distributed at railway stations both as food and as seed stock. The crop thrived in regions such as Maine, Minnesota, and along Colorado’s rivers, so that by 1850, the area under potato cultivation had surpassed 200,000 hectares. Its advantage over cereals lay in its ability to produce acceptable yields under short daylight hours and in relatively poor soils.

Section Three: Impact on Population Growth and Famine Reduction

One of the most important metrics for assessing the potato’s impact is population growth before and after its widespread adoption in various regions. Historical studies demonstrate that between 1750 and 1850, areas of Western Europe with extensive potato cultivation experienced 25 to 30 percent higher population growth compared to regions dependent solely on cereals. On average, each household cultivating one hectare of potatoes could generate an additional 2,500 kilocalories per day—enough extra food to sustain one adult.

A similar pattern emerged in Scandinavia: in Norway and Sweden—where climatic conditions are colder than in England—potato yields reached up to 15 tons per hectare, compared to a maximum of three to four tons for wheat. This five‑fold advantage led to a 60 percent reduction in winter mortality by 1850. In Ireland, although overreliance on a single potato variety precipitated the Great Famine of 1845–1849, in the preceding period, the potato as a staple food had continuously supported population growth among the poor up to 1840.

In British India, data published by the Indian Statistical Office in 1901 showed that in states such as Maharashtra and Punjab, potato cultivation raised the daily caloric threshold for nearly 30 million people and cut famine risk by 50 percent during the 1870s. However, in regions with limited potato genetic diversity, periodic outbreaks of fungal diseases like late blight in the late nineteenth century inflicted serious crop losses.

Section Four: Economic and Industrial Dimensions

The potato’s value extended beyond human consumption to livestock feed and as a raw material for processing industries such as starch and alcohol production. In nineteenth‑century France and Germany, starch factories extracted potato starch to manufacture items like paper, artificial silk fabrics, and pharmaceuticals. Over time, these industries evolved into early petrochemical sectors, since potato starch can serve as a precursor for producing ethanol and biodegradable plastics.

During Britain’s Industrial Revolution, the reliable supply of calories from potatoes enabled urban laborers to sustain physically demanding work in mines and factories. Some historians argue that the three major food shortages of 1766–1768, 1793–1795, and 1812–1813 would have led to social collapse and a deep economic recession without the potato. By providing a cheap, rapid‑energy reserve, it played a pivotal role in stabilizing the nascent capitalist economy.

In the late twentieth century, a global potato market emerged, with the European Union alone controlling over one‑third of world exports and imports. Producers in the Netherlands, Germany, and France earned substantial export revenues by supplying improved cultivars and precision‑farming technologies.

Section Five: Future Outlook and Lessons for Sustainable Development

Today, with climate change and increasingly erratic rainfall patterns, the potato’s status as a drought‑tolerant crop with a broad temperature range has become more critical than ever. Researchers at institutions such as the International Potato Center (CIP) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) are applying biotechnology and genome‑editing tools (CRISPR‑Cas9) to develop varieties simultaneously resistant to heat, salinity, and pests.

Meanwhile, urban agriculture initiatives and novel cultivation methods—such as hydroponics and hybrid hydroponic systems with closed‑loop irrigation—have emerged, enabling potato production on rooftops, in greenhouses, and even in desert environments without soil and with minimal water use. These models could play a vital role in addressing food crises in major cities and arid regions lacking suitable farmland.

Economically, value‑added potato products—such as chips, frozen mashed potatoes, starches, and biodiesel—continue to drive employment and foreign exchange earnings in developing countries that export these processed goods.

Ultimately, the potato’s historical experience offers invaluable lessons for policymakers and sustainable‑development advocates:

- Genetic Diversity Is Crucial: Maintaining a wide range of cultivars and preserving local seed stocks is key to preventing agricultural disasters.

- Invest in Agricultural Infrastructure: Railroads, seed and product transport networks, and climate‑controlled storage facilities are fundamental.

- Coordinate Food and Health Policies: Integrating proper nutrition with healthcare and education services enhances resilience.

- Embrace Technological Innovation: Leveraging biotechnology and precision‑agriculture tools will sustain and expand potato’s role in global food security.

Thus, the potato has not only served as a stable, economy‑boosting food source in the past but also stands poised to become a cornerstone of twenty‑first‑century strategies for ensuring adequate nutrition and sustainable development.

Section Six: Cultural and Culinary Role of the Potato

Throughout history, the potato has occupied a special place in the culinary cultures of diverse nations. In Europe, mashed potatoes have become a staple family dish, commonly served alongside roasted meat and vegetables. Belgium is famed for its Belgian fries—a twice‑fried preparation served with a variety of sauces such as mayonnaise or malt vinegar.

In Latin America, Peru celebrates “causa,” a layered cold dish of seasoned potatoes filled with avocado and chicken or fish, showcasing indigenous culinary creativity. In Mexico, the potato taco—crispy corn shells filled with spiced mashed potatoes—has become a beloved street food.

In Asia, India’s aloo gobi—potatoes and cauliflower cooked with curry spices and served with bread or rice—enjoys widespread popularity across the subcontinent. In northern China, shredded potatoes are tossed with soy sauce and vinegar to create a cold, spicy salad.

Beyond cuisine, the potato appears in art and literature as well. Romantic‑era European poets and writers hailed it as a symbol of simple peasant life, and realist painters often depicted fieldworkers harvesting potatoes to celebrate human labor and the bond between people and the land.

Every year, numerous festivals honor the potato’s significance. For example, Germany’s autumn Kartoffelfest (“Potato Festival”) features stalls offering innovative potato‑based dishes and provides a platform for showcasing new processing and cooking techniques.

This cultural dimension elevates the potato far beyond a mere foodstuff, making it a unifier of peoples and generations and a mirror of human ingenuity and diversity.

Section Seven: Conclusion

In summary, the potato—through its high yields, adaptability to diverse climates, and outstanding nutritional value—has played an unparalleled role in ensuring food security for vast populations throughout history. This humble yet powerful tuber:

- Prevented widespread famine and fueled population growth across Europe, Asia, and the Americas.

- Generated economic value in processing industries, enabling labor shifts from agriculture to manufacturing and services.

- Enhanced agricultural resilience through its multiple uses—as human food, animal feed, and industrial raw material.

- Served as a cultural touchstone, inspiring culinary traditions, art, and communal celebrations..

Looking ahead, with the adoption of innovative agricultural technologies and the safeguarding of genetic diversity, the potato can continue to underpin global food‑security and sustainable‑development strategies in the twenty‑first century. Policymakers, researchers, and agricultural practitioners must draw on historical lessons and modern biotechnological and digital tools to harness this vital crop in the service of nutritious food, resilient economies, and vibrant cultures.

Ultimately, the potato stands not merely as an agricultural commodity but as a symbol of humanity’s capacity for innovation, cooperation, and harmony with nature—a call to imagine a future in which sustainable agriculture and universal access to food are both achievable and widespread.

External References for the History of the Potato

- For a detailed historical overview, see FAO’s article on the potato’s journey through history .

- Smithsonian Magazine explores its global impact: “How the Potato Changed the World” on Smithsonian .

Leave a Reply