Introduction

Black holes are among the most enigmatic and awe-inspiring phenomena in the cosmos. They are regions of spacetime where gravity is so powerful that nothing—not even light—can escape their grasp. The term “black hole” was popularized in the 1960s, but the concept traces back to the 18th century when scientists like John Michell and Pierre-Simon Laplace theorized about objects with gravity so strong that light could not break free. Today, black holes are not mere speculation but observable entities that shape our understanding of the universe.

A black hole forms when a massive star collapses under its own gravity at the end of its life cycle, or through other processes like the merger of smaller black holes. If the collapsing core is sufficiently massive—typically more than three times the mass of our Sun—it compresses into an infinitely small point called a singularity, surrounded by a boundary known as the event horizon. Beyond this boundary, escape is impossible. Black holes vary greatly in size and mass, and they play a critical role in the structure and evolution of galaxies, influencing everything from star formation to the motion of cosmic objects. In this article, we will explore their formation, types, structure, and effects, ensuring the journey remains engaging and accessible.

Formation of Black Holes

Black holes are born from cataclysmic events, most commonly the death of massive stars. Stars shine by fusing hydrogen into helium in their cores, releasing energy that counteracts their own gravity. For a star like our Sun, this process ends with a transformation into a white dwarf. However, for stars with masses at least eight times that of the Sun, the finale is far more dramatic. When such a star exhausts its nuclear fuel, its core collapses inward in seconds, triggering a supernova explosion that blasts its outer layers into space. If the remaining core exceeds about 2.5 to 3 times the Sun’s mass, it collapses into a singularity, giving birth to a black hole.

Supermassive black holes, found at the centers of galaxies, likely form differently—possibly through mergers of smaller black holes or the collapse of massive gas clouds in the early universe. Primordial black holes, a theoretical type, might have formed from density fluctuations shortly after the Big Bang, though they remain undetected.

Types of Singularities

Singularities come in various forms, each defined by its mass, size, and role in the universe. Let’s explore these fascinating types in detail.

Stellar-mass singularities are the most common variety, formed from the remnants of massive stars. These singularities have masses ranging from about 2 to 150 times that of the Sun, making them relatively small compared to their larger counterparts. Despite their modest mass, they are incredibly dense, with radii typically around 30 kilometers—about the size of a small city. You’ll often find them scattered throughout galaxies, especially in binary systems where they orbit a companion star. In these systems, they pull in matter from their partner, creating a glowing accretion disk that emits X-rays, which is how we often detect them. Cygnus X-1, the first confirmed singularity, is a stellar-mass example discovered in 1971.

Next, there are intermediate-mass singularities, a less certain but intriguing category. These singularities have masses between 100 and 10,000 times that of the Sun, placing them between stellar-mass and supermassive varieties. Their radii might stretch to about 1,000 kilometers, roughly the size of Earth. Scientists suspect they could form in dense stellar environments like globular clusters, where multiple stellar-mass singularities might merge over time. While their existence isn’t as well-established, they may act as a stepping stone in the growth of larger singularities, making them a key focus of current research.

Supermassive singularities are the titans of this family, with masses ranging from millions to billions of solar masses. These giants anchor the centers of most galaxies, including our own Milky Way, where Sagittarius A* reigns with a mass of about 4 million solar masses. Their radii can vary widely, from 0.001 to 400 astronomical units (AU)—where 1 AU is the distance from Earth to the Sun. For instance, Sagittarius A*’s event horizon spans about 0.08 AU, roughly the distance from the Sun to Mercury. These singularities wield immense influence, shaping galaxy evolution by affecting star formation and the motion of stars. They likely grow through mergers or by gobbling up vast amounts of gas and dust over billions of years.

Finally, ultramassive singularities represent the largest known type, with masses exceeding 10 billion solar masses. Found in the cores of giant elliptical galaxies, these colossal objects have radii that can stretch over 1,000 AU, dwarfing even supermassive singularities. They are thought to form through the merger of galaxies and their central singularities, offering a glimpse into the most extreme processes in the cosmos. Though rare, their sheer scale makes them a captivating subject of study.

Each type of singularity—from the compact stellar-mass to the sprawling ultramassive—reveals a different facet of the universe’s complexity, enriching our understanding of cosmic mysteries.

Structure of a Black Hole

To truly appreciate black holes, we must delve into their internal structure, which, while invisible, is revealed through their effects on surrounding matter and light.

At the heart of every black hole lies the singularity, a point of infinite density where all the black hole’s mass is concentrated. Here, spacetime curvature becomes infinite, and the laws of physics as we know them break down. For a non-rotating black hole, the singularity is a single point; for a rotating one, it may take the form of a ring. This singularity is hidden behind the event horizon, making it impossible to observe directly.

Surrounding the singularity is the event horizon, the defining feature of a black hole. Often described as the point of no return, it is the boundary beyond which nothing—not even light—can escape the black hole’s gravitational pull. For a non-rotating black hole, the event horizon is spherical and is known as the Schwarzschild radius, calculated as approximately 2.95 kilometers per solar mass. So, for a black hole with the Sun’s mass, this radius would be about 3 kilometers. Importantly, the event horizon isn’t a physical surface but a mathematical boundary where the escape velocity equals the speed of light.

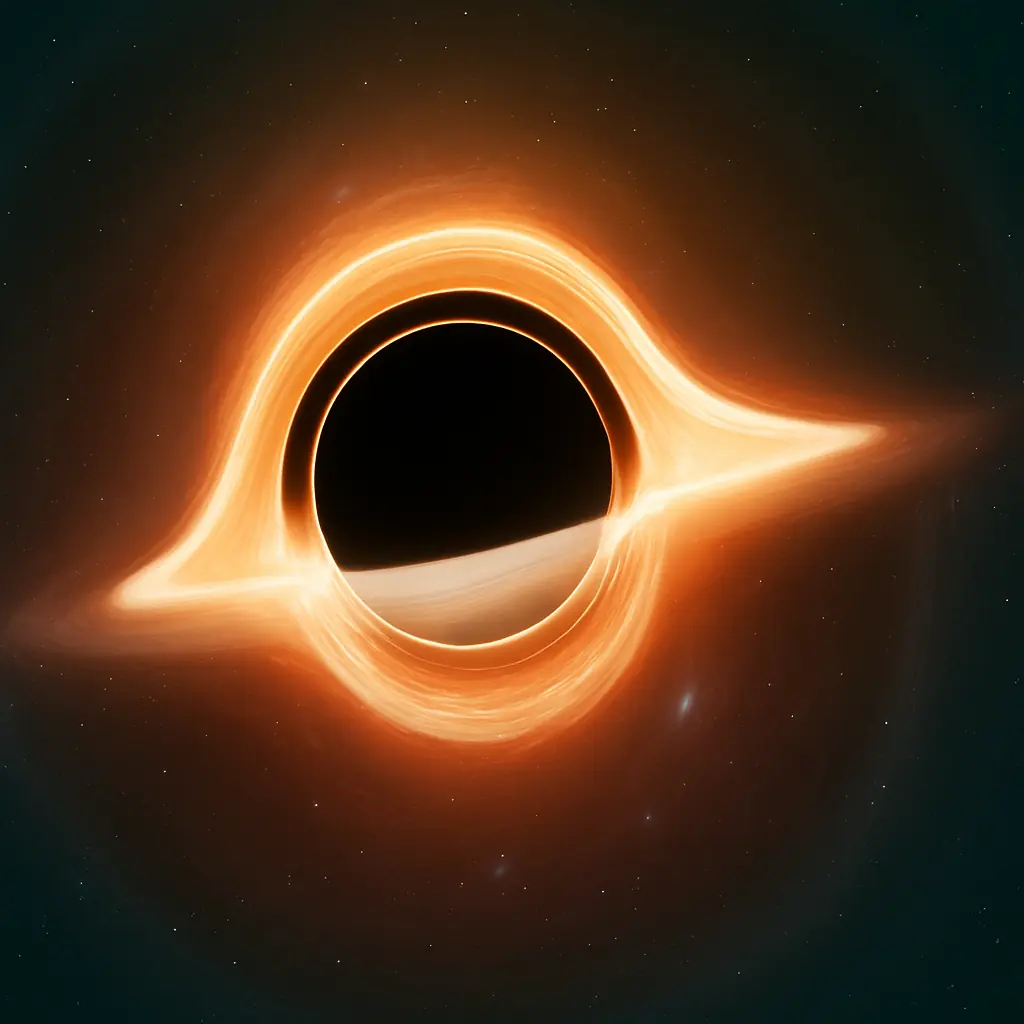

Just outside the event horizon is the photon sphere, a region where light can orbit the black hole. For a non-rotating black hole, this sphere is located at 1.5 times the Schwarzschild radius. Light entering this region can either fall into the black hole or escape, creating a bright ring around the black hole’s shadow—a phenomenon famously captured in the first black hole images by the Event Horizon Telescope.

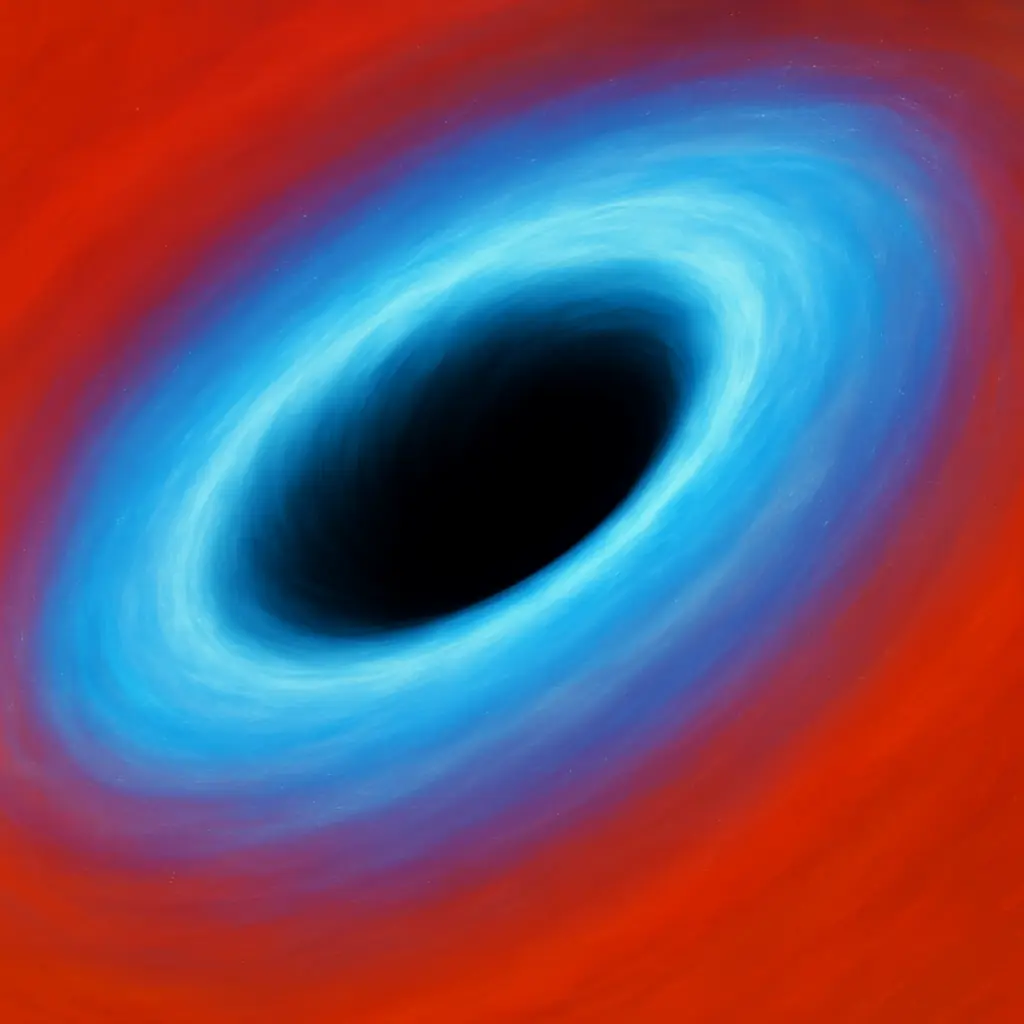

For rotating black holes, there’s an additional region called the ergosphere, located outside the event horizon. Within the ergosphere, spacetime is dragged along with the black hole’s rotation, forcing any object to move in the same direction. This region allows for unique physical processes, such as the extraction of energy from the black hole’s rotation via the Penrose process.

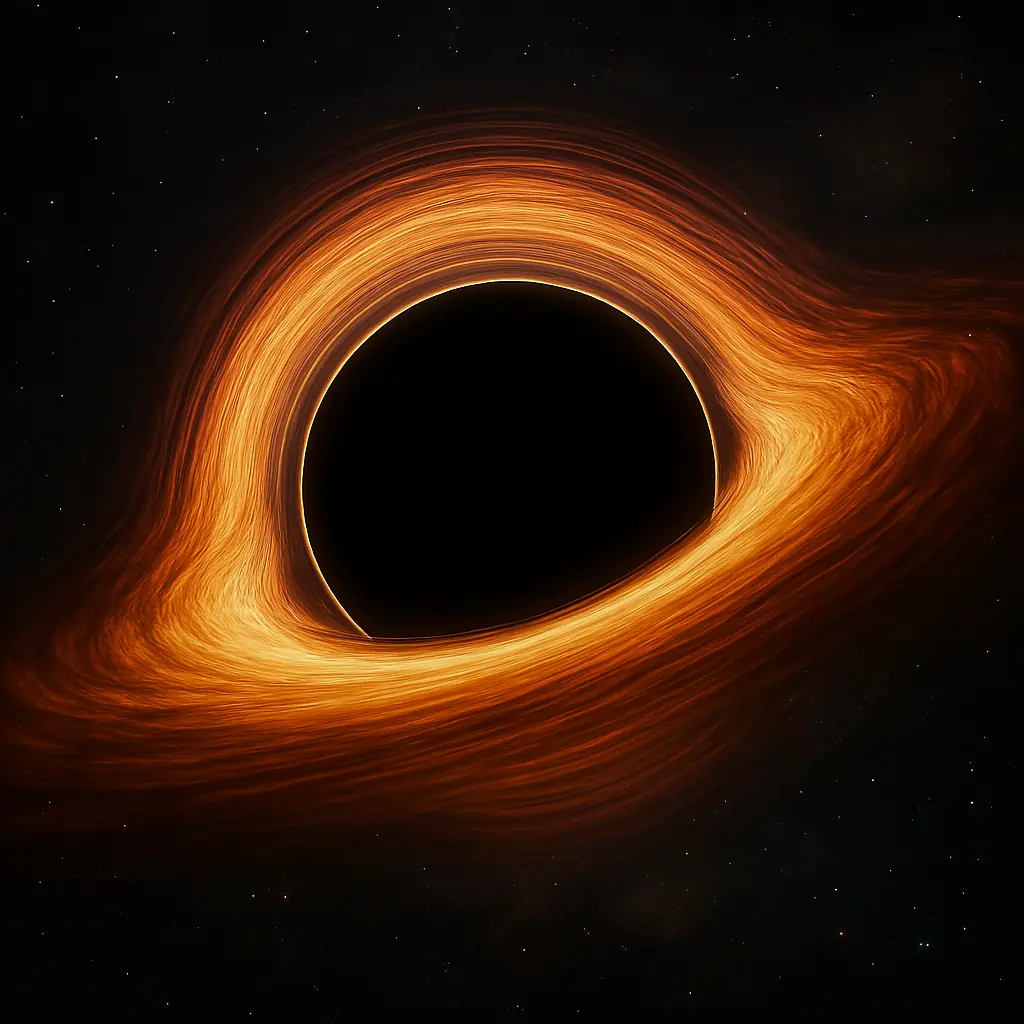

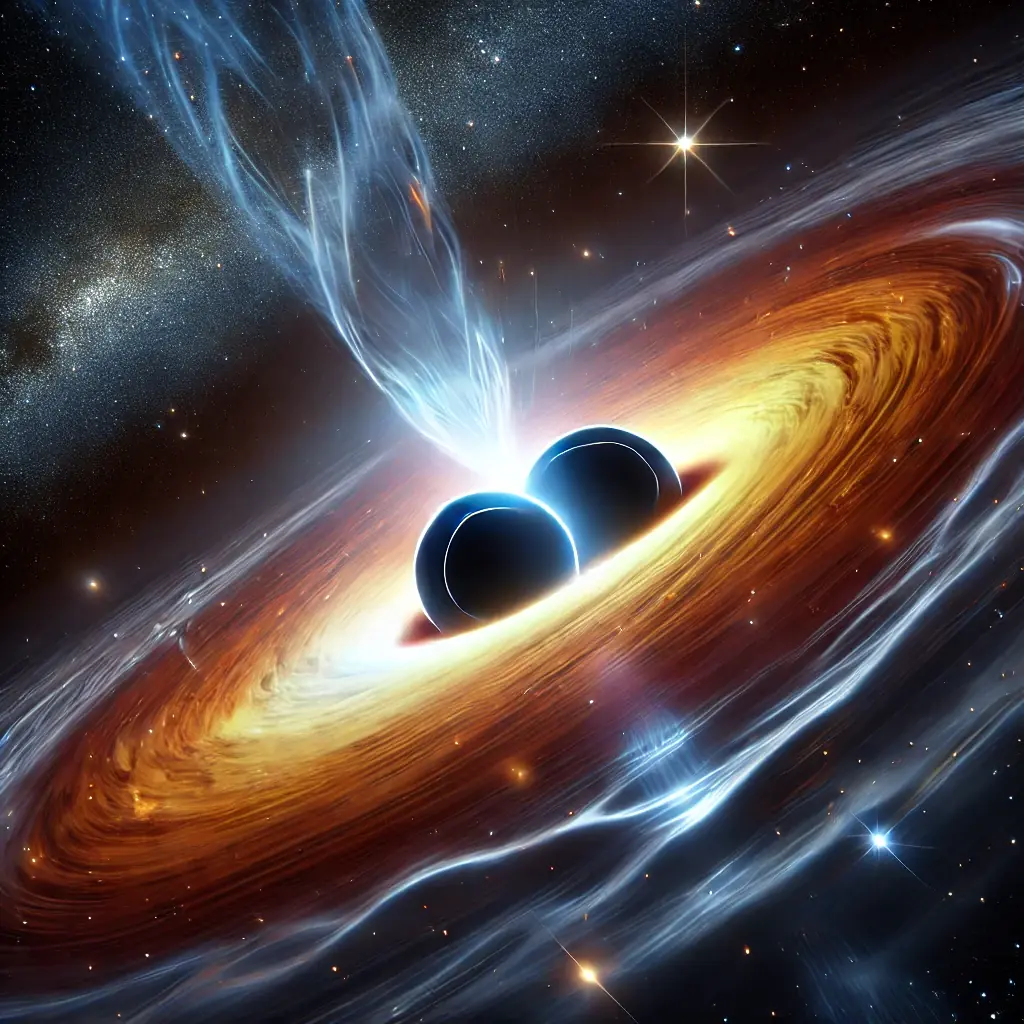

Many black holes are also surrounded by an accretion disk, a swirling disk of gas, dust, and other material spiraling inward. As this material falls toward the black hole, it compresses and heats up due to friction, emitting radiation across the electromagnetic spectrum, including X-rays. These disks can outshine entire galaxies in some cases, as seen in quasars powered by supermassive black holes.

Gravitational Effects of Black Holes

The gravitational pull of black holes is so intense that it warps the fabric of spacetime, producing extraordinary effects on nearby objects and light.

One dramatic consequence is tidal forces, which arise from the steep gradient in gravitational strength. Near a stellar-mass black hole, these forces stretch objects into long, thin shapes—a process vividly termed spaghettification. Imagine an astronaut falling toward a black hole feet-first: the gravity at their feet would be far stronger than at their head, stretching them out before they even reach the event horizon. For supermassive black holes, with their larger event horizons, these tidal forces are less extreme near the boundary, allowing objects to approach closer before being torn apart.

Another striking effect is gravitational lensing, where a black hole’s gravity bends light from objects behind it. This bending can magnify or distort the appearance of distant stars and galaxies, sometimes creating arcs or multiple images of the same object. Astronomers use this phenomenon to study the universe and even detect black holes that aren’t emitting radiation, as the lensing reveals their presence through the altered paths of light.

On a grand scale, supermassive black holes at galaxy centers exert a commanding influence. They govern the orbits of nearby stars—evidence for Sagittarius A* in the Milky Way comes from tracking stars moving at incredible speeds near the galactic core. These black holes also regulate galaxy evolution. When matter falls into them, it releases energy in powerful jets or winds, heating surrounding gas and preventing it from collapsing into new stars, thus controlling the galaxy’s star formation rate.

Black Holes in the Universe

Black holes are not rare curiosities; they are fundamental to the cosmos. Nearly every large galaxy harbors a supermassive black hole at its heart, driving its development. The Milky Way’s Sagittarius A*, with a mass of 4 million Suns, is a relatively modest example compared to the 6.5-billion-solar-mass giant at the center of the M87 galaxy. Stellar-mass black holes, meanwhile, dot galaxies in greater numbers, often found in binary systems or regions where massive stars once lived and died.

We observe black holes through their interactions with their surroundings. Stellar-mass black holes in binary systems reveal themselves by pulling matter from a companion star, forming an accretion disk that glows with X-rays. Supermassive black holes announce their presence through the intense radiation of quasars or the rapid orbits of nearby stars. In 2019, the Event Horizon Telescope captured the first image of a black hole’s shadow in M87, followed by an image of Sagittarius A* in 2022, offering direct visual evidence of these objects. Additionally, the 2015 detection of gravitational waves by LIGO—ripples in spacetime from two stellar-mass black holes merging—confirmed their existence in a new way, ushering in the era of gravitational wave astronomy.

Theoretical Aspects of Black Holes

Black holes are more than physical objects; they are windows into the fundamental nature of reality. They emerge from Einstein’s general relativity, which describes gravity as spacetime curvature. The theory predicts black holes perfectly, and observations—like the tight orbits of stars around Sagittarius A*—match these predictions with stunning accuracy, reinforcing our confidence in relativity.

Yet black holes also challenge physics. Stephen Hawking’s 1974 breakthrough showed they emit radiation due to quantum effects near the event horizon. Known as Hawking radiation, this process involves particle-antiparticle pairs forming at the boundary: if one falls in and the other escapes, the black hole loses a tiny bit of mass. Over vast timescales—10^64 years for a solar-mass black hole—this could cause it to evaporate entirely, though no one has observed it yet due to the faintness of the radiation.

This leads to the black hole information paradox. Quantum mechanics insists information cannot be destroyed, but if a black hole evaporates, what happens to the information about the matter it consumed? Early theories suggested it was lost, clashing with quantum principles. Modern ideas, like the holographic principle, propose the information is encoded on the event horizon, but the debate persists, driving efforts to unite quantum mechanics and gravity.

Impact on Our Understanding of the Universe

Black holes have transformed cosmology and physics. Supermassive black holes are engines of galaxy formation, their energy outputs shaping how galaxies grow and evolve. Stellar-mass black holes, through their births in supernovae and mergers detected via gravitational waves, reveal the life cycles of stars and the dynamics of dense stellar environments.

They also test the limits of our theories. General relativity holds up near black holes, but the singularities inside them—where gravity becomes infinite—suggest a need for a quantum theory of gravity. The information paradox further highlights this gap, pushing scientists toward new frameworks like string theory or loop quantum gravity.

Beyond science, black holes captivate the imagination, appearing in films and books as portals or destroyers. Yet their real role is far richer: they are architects of the cosmos, weaving gravity, matter, and energy into the universe we see today.

Leave a Reply