Introduction

Honey, a sweet viscous liquid, has been valued for centuries as food and medicine. Bees produce honey by collecting nectar and transforming it with enzymes. For example, a single jar requires bees to visit up to three million flowers. The health benefits of honey, including antioxidant and antimicrobial properties, intrigue researchers. This article explores honey’s composition, health effects, and applications, both traditional and modern. However, its acceptance in clinical practice remains limited. Honey’s role in nutrition and therapy is profound yet complex.

The health benefits of honey stem from its unique compounds, like flavonoids. Scientific studies confirm its efficacy in wound healing and cough relief. Despite historical use, modern medicine hesitates to fully endorse it. Phenolic compounds in honey contribute to its therapeutic potential. Thus, understanding honey’s science clarifies its value. This analysis balances its benefits with practical limitations.

Chemical Composition of Honey

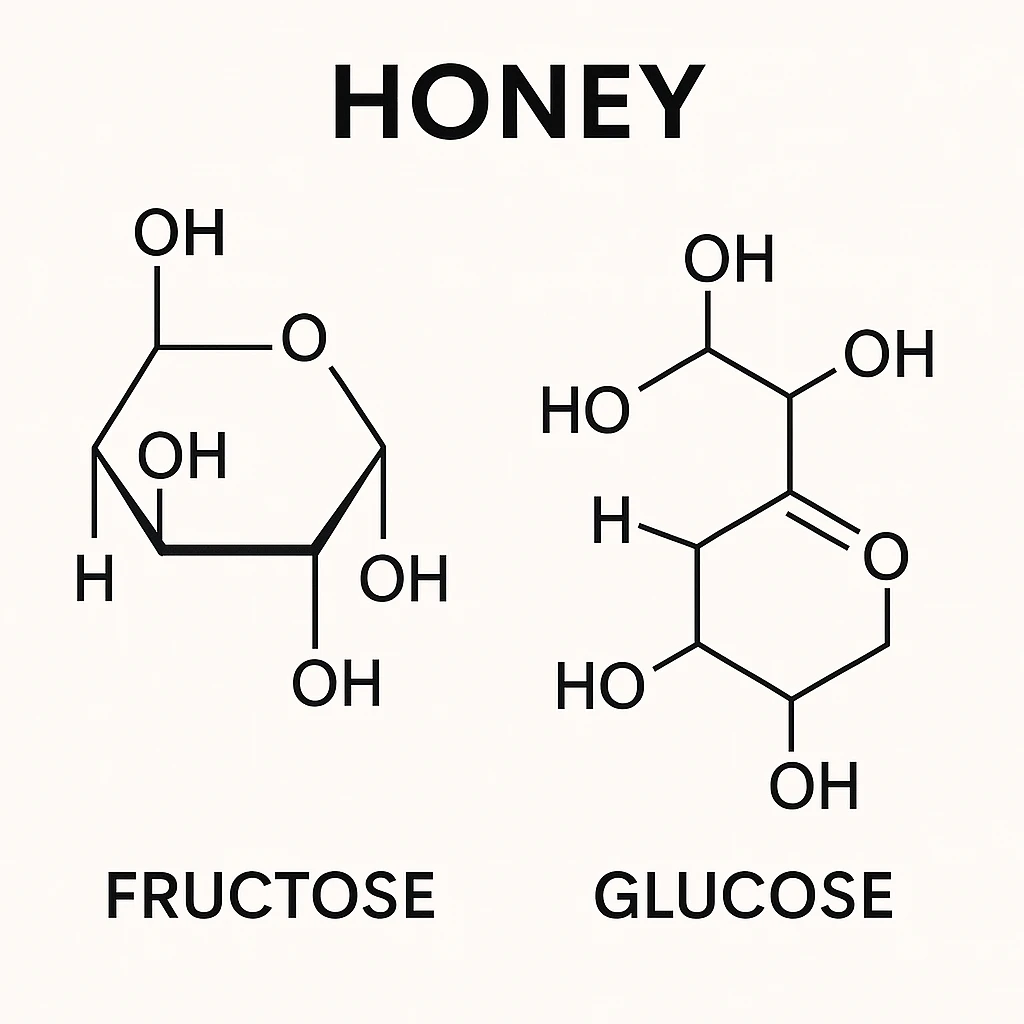

Honey’s composition varies by floral source but includes sugars and bioactive compounds. Fructose (38–40%) and glucose (31%) dominate, providing sweetness and energy. Water content, typically 17–20%, affects viscosity. Phenolic compounds in honey, such as quercetin, were identified as key antioxidants. These compounds neutralize free radicals, supporting health. Enzymes like glucose oxidase produce hydrogen peroxide, enhancing antimicrobial effects. Trace minerals, like potassium, add nutritional value.

Minor components, including volatile oils, contribute to honey’s aroma and flavor. Polyphenols are influenced by the nectar’s botanical origin. For instance, darker honeys like manuka contain higher phenolic levels. The antimicrobial properties of honey rely on low water activity and high acidity. These traits create an inhospitable environment for microbes. Thus, honey’s chemical profile underpins its therapeutic uses. Research continues to uncover its bioactive complexity.

Honey’s composition was analyzed to understand its stability and shelf life. Natural preservatives, like low water content, prevent spoilage. Organic acids maintain a pH of 3.2–4.5, inhibiting bacterial growth. These factors ensure honey’s longevity without artificial additives. Chemical diversity drives its health benefits. However, variations challenge standardization for medical use.

Health Benefits of Honey

The health benefits of honey include antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory effects. Flavonoids and phenolic acids neutralize oxidative stress, reducing chronic disease risk. For example, studies link honey to improved cardiovascular health by lowering LDL cholesterol. The antimicrobial properties of honey, effective at 10–50% concentration, combat bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus. These effects stem from hydrogen peroxide and methylglyoxal. Honey also soothes coughs, outperforming some over-the-counter remedies. Its role in nutrition supports immune function.

Clinical trials confirm honey’s efficacy in wound healing. Its high osmolarity draws moisture from wounds, reducing infection. Anti-inflammatory compounds decrease swelling and pain. However, evidence for broader claims, like cancer prevention, remains weak. The health benefits of honey are promising but not universal. Infants under one face botulism risk from raw honey. Thus, careful application is essential.

Honey’s benefits were studied for metabolic health, showing improved glycemic control. Polyphenols may enhance insulin sensitivity in some populations. Yet, high sugar content requires moderation in diabetic diets. Therapeutic uses of honey continue to evolve. Research gaps limit its integration into mainstream medicine. Balancing benefits with risks guides its safe use.

Traditional and Modern Uses

Honey has been used traditionally for millennia across cultures. Ancient Egyptians applied it to wounds, while Ayurveda recommends it for digestion. Its antimicrobial properties of honey supported its use in preserving food. Folk remedies often combine honey with herbs for colds. These practices, rooted in observation, align with modern findings. Today, honey is marketed as a natural sweetener and health supplement. Its cultural significance endures in rituals and cuisines.

Modern applications focus on clinical settings. Medical-grade honey, like manuka, treats chronic wounds and burns. For instance, hospitals use honey dressings to reduce healing time. The health benefits of honey extend to oral health, with studies showing reduced plaque. Over-the-counter products, like honey-based lozenges, target sore throats. However, unverified claims about curing Alzheimer’s lack evidence. Therapeutic uses of honey require rigorous validation.

Honey’s modern use was expanded by research into its prebiotic effects. It supports gut microbiota, promoting digestive health. Cosmetic industries incorporate honey in skincare for its moisturizing properties. Yet, standardization challenges persist due to compositional variability. Regulatory hurdles limit clinical adoption. Honey’s versatility drives innovation, but evidence-based practice is critical.

Leave a Reply