Introduction

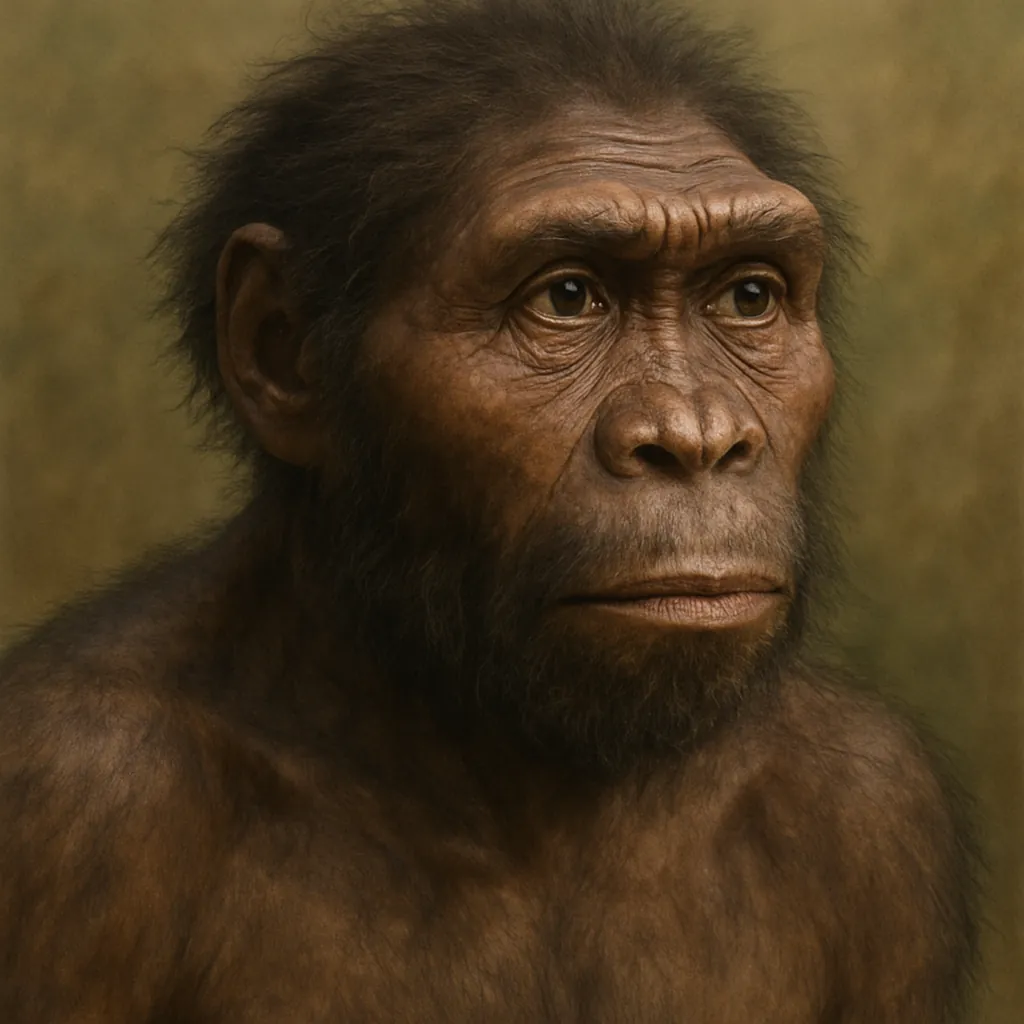

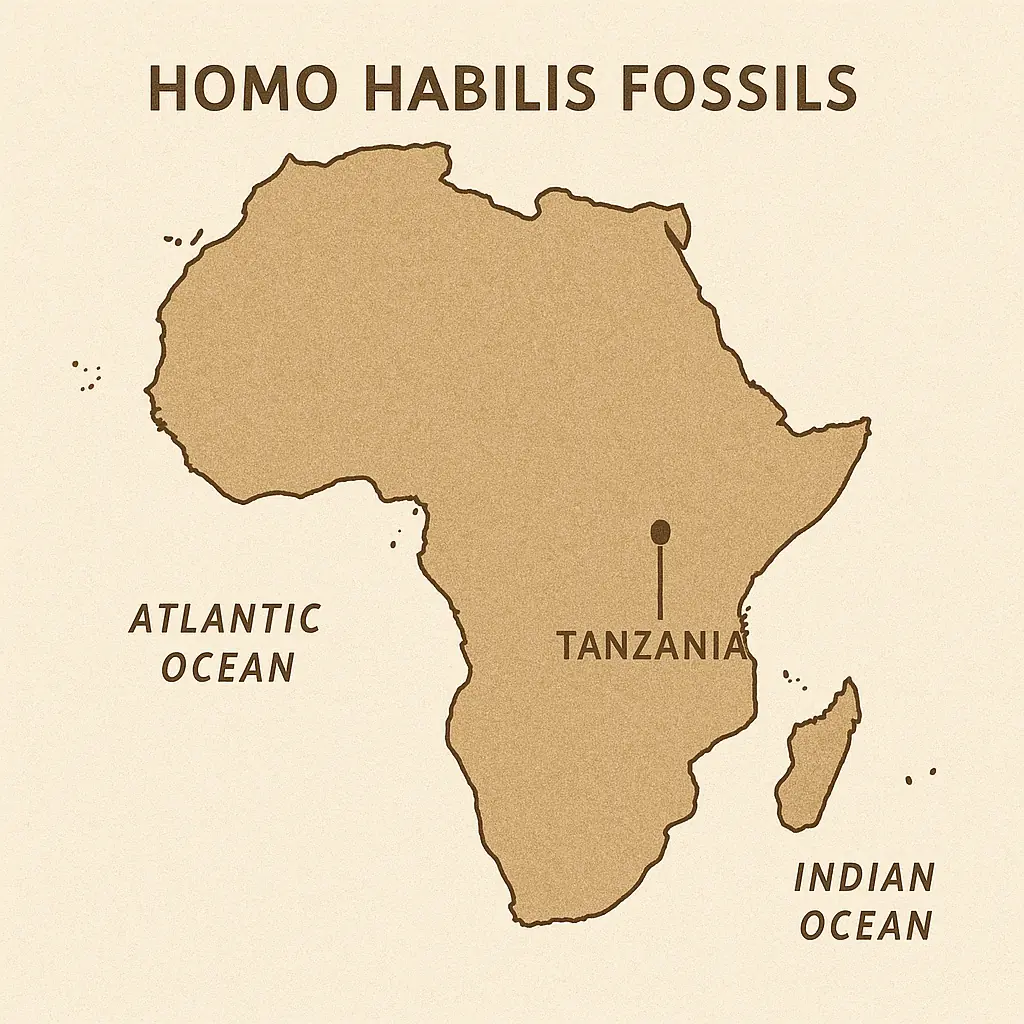

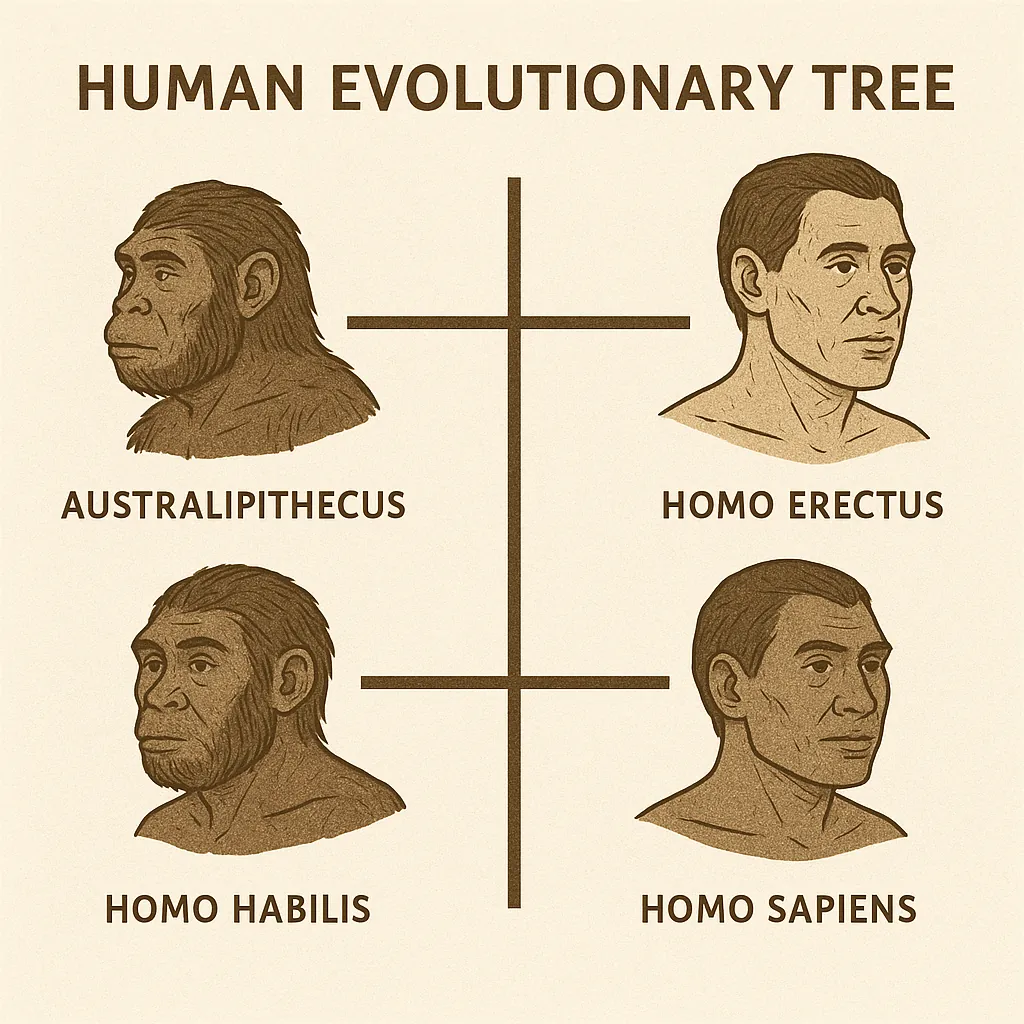

Homo habilis evolution, starting around 2.4 million years ago in East Africa, marks a turning point in the human story. Known as the “handy man,” this species was the first Homo, advancing beyond Australopithecus with a larger brain and tool-making skills. Fossils from sites like Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, reveal a blend of ape-like and human-like features, connecting earlier hominins to later species like Homo erectus. This advance introduced gains in intelligence, diet, and behavior that shaped early humans. This article explores how Homo habilis differed from its Australopithecus ancestors.

In 1960, Louis and Mary Leakey uncovered Homo habilis fossils, officially named in 1964, sparking questions about human origins. Was this tool-maker a true Homo or an advanced Australopithecus? With a brain larger than its predecessors and hands suited for crafting, Homo habilis evolution was a pioneering step. Its story, lasting until about 1.5 million years ago, offers insights into our roots. Let’s examine how this early human earned its place in our lineage.

Roots of a New Hominin

Homo habilis evolution began around 2.4–2.3 million years ago, likely stemming from Australopithecus species like Australopithecus africanus or Australopithecus afarensis. These ancestors walked upright but had small brains (400–500 cm³) and long arms for climbing. Homo habilis retained a small body and some climbing ability but boosted its brain size to 510–700 cm³, suggesting improved cognitive skills. The Australopithecus transition was gradual, driven by Africa’s cooling climate, which turned forests into savannas. Fossils like OH 7 from Olduvai Gorge highlight this shift.

Diet played a key role in moving away from Australopithecus. Those earlier hominins ate tough plants, using large jaws and teeth for grinding. Homo habilis was omnivorous, consuming plants, tubers, and likely scavenging meat, as bone cut marks suggest, though isotopes show a mixed diet. Smaller molars, seen in fossils like KNM-ER 1813, indicate less reliance on hard plants. This varied diet likely supported brain growth by providing more energy.

Africa’s grasslands, expanding around 2.5 million years ago, shaped this transition. Open landscapes demanded new ways to find food, pushing hominins to adapt. Fossils from Koobi Fora, Kenya, and Hadar, Ethiopia, show Homo habilis thrived until about 1.5 million years ago. It combined Australopithecus traits, like long arms, with new ones, like tool-making, bridging to later humans. This slow change was a critical step in our lineage.

Thinking Takes Shape

Homo habilis evolution brought a notable brain size increase, a sign of early human intelligence. Its brain averaged 610 cm³ (510–700 cm³), with skulls like KNM-ER 1470 reaching ~700–775 cm³, compared to Australopithecus’s 400–500 cm³. More brain folds supported better planning and problem-solving, aiding survival in the savanna, like finding food or avoiding predators. These thinking skills were basic but gave Homo habilis an edge. Fossils like OH 24 show a rounder skull, reflecting brain changes.

A varied diet likely fueled this brain growth. Homo habilis ate meat, tubers, and plants, providing calories for a larger brain, though isotopes confirm an omnivorous diet, not just meat-focused. Group living also boosted intelligence, as sharing food and managing relationships required mental effort. Early human intelligence appeared in tool-making and scavenging strategies. Still, Homo habilis’s cognitive abilities were far from modern human levels.

Was Homo habilis much smarter than Australopithecus? Some argue the difference was modest, as Australopithecus may have used simple tools. Fossils like OH 62, with a small brain and long arms, suggest Homo habilis was still developing its cognitive skills. Early human intelligence was an early advance, not a leap, compared to Homo erectus later. This brain growth was a crucial but modest step for survival.

Tools of Survival

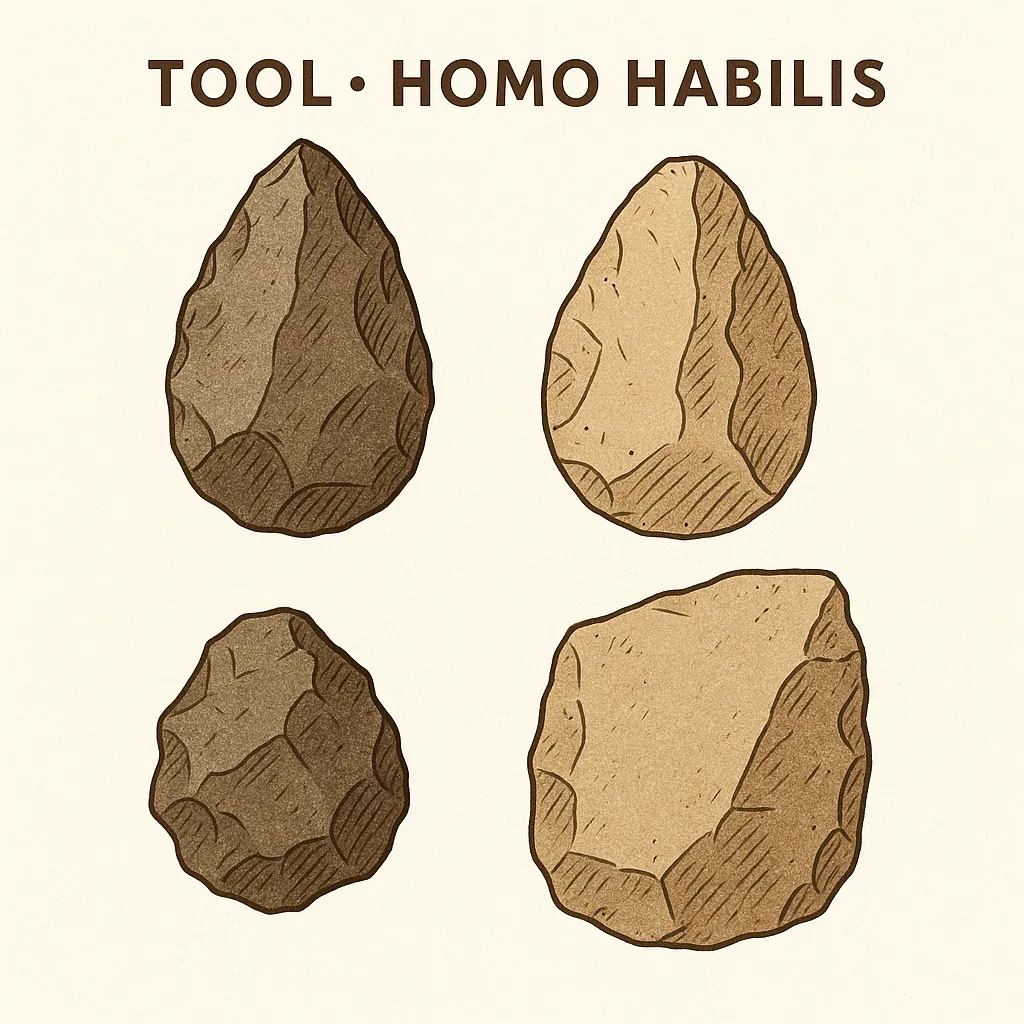

The shift to tool-making defines Homo habilis’s legacy, earning it the “handy man” name. The earliest tools, from Lomekwi 3 in Kenya (3.3 million years ago), predate Homo and are not Oldowan, likely made by Australopithecus or similar hominins. Homo habilis refined this with Oldowan tools, dated 2.9–1.5 million years ago, found in Nyayanga, Kenya. These stone flakes and cores cut meat, cracked bones for marrow, or processed plants, showing planning. The stone tool culture marked a cognitive step. Fossils like OH 7 suggest hands adapted for tool work.

Oldowan tools required precision. Homo habilis chose stones like flint or basalt, striking them to create sharp edges, as seen in Koobi Fora finds. Unlike Lomekwi 3’s simpler tools, Oldowan tools were systematic, with Olduvai Gorge showing routine use. The stone tool culture was a hallmark of Homo habilis’s behavior, though some suggest Australopithecus garhi used similar tools. Homo habilis made tool-making a regular practice.

Homo habilis evolution tied tools to survival. They accessed calorie-rich foods like marrow, supporting brain growth, as smaller teeth in KNM-ER 1813 suggest less need for chewing tough plants. Tools aided scavenging, helping compete with predators like hyenas. This advance was a clear step beyond Australopithecus’s simpler methods. The tool-making shift showed planning and adaptability in a changing world.

Adapting to the Savanna

This advance introduced physical differences from Australopithecus, though Homo habilis stayed small, standing 1.2–1.35 m (~4–4.4 ft) and weighing 20–37 kg. Its skull was less forward-jutting, and teeth were smaller than Australopithecus’s large grinders, reflecting an omnivorous diet. Fossils like OH 62 show long arms for some tree-climbing, but a human-like foot arch in OH 8 indicates better walking. Homo habilis was more ground-adapted than Australopithecus. It balanced ancestral and new traits.

Lifestyle shifts set Homo habilis apart. Australopithecus lived partly in trees, using bipedalism but climbing often. Homo habilis focused on ground-based scavenging and group living, using tools to access meat or tubers, as bone cut marks show. Its omnivorous diet included scavenging, unlike Australopithecus’s plant-heavy focus. It lacked the build for long treks like Homo erectus, but the Australopithecus transition favored savanna life.

Africa’s grasslands, expanding 2.5 million years ago, drove these changes. Fossils from Hadar and Koobi Fora show Homo habilis adapted to open areas, where tools and teamwork were vital. It still climbed trees, as OH 62’s arms suggest, but walked more efficiently than Australopithecus. The Australopithecus transition made Homo habilis a ground-dweller with new survival strategies, a step toward later humans.

Debates and Questions About Homo habilis

Homo habilis evolution sparks debate about its place in our lineage. Discovered in 1960 with OH 7 and named in 1964 by Louis Leakey’s team, it was seen as a Homo ancestor to Homo erectus. But its ape-like traits, like OH 62’s small brain (510 cm³) and long arms, lead some to classify it as Australopithecus habilis. A 2023 dental study shows Homo habilis differs from Homo rudolfensis, supporting separate species. The Australopithecus transition remains unclear, complicating Homo’s start.

Was Homo habilis one species or multiple? Skulls like KNM-ER 1470 (~700–775 cm³) and KNM-ER 1813 (510 cm³) vary widely, suggesting Homo rudolfensis as distinct. Teeth in OH 16 resemble Australopithecus more than later Homo, indicating primitive roots. This variation implies Homo habilis involved several hominins coexisting, not a single line. The debate challenges its role as a direct ancestor.

How advanced was Homo habilis? Some argue its intelligence was close to Australopithecus, since Lomekwi 3 tools (3.3 Ma) predate Homo. Jaw marks from toothpick use show some ingenuity, but not a major leap. This advance raises questions about tools, brains, and human traits, with fossils like those in Koobi Fora offering partial answers. Homo habilis is a hominin caught between earlier ancestors and future humans.

Leave a Reply