Introduction

Flies. They buzz around your kitchen, land on your food, and dodge your swatter like tiny acrobats. But there’s more to these critters than their pesky habits. Housefly biology reveals a world of intricate designs and surprising roles in nature. These insects, often dismissed as nuisances, are key players in ecosystems and have a history stretching back millions of years. Let’s dive into what makes flies so unique and why they’re worth a closer look.

From lightning-fast reflexes to thriving in almost any environment, flies are marvels of evolution. Understanding housefly biology sheds light on their behaviors and helps us appreciate their place in the world. Whether you’re curious about their anatomy, ecological contributions, or how they’ve evolved, this article unpacks the story of flies in a way that’s easy to grasp and maybe even a bit fun.

Anatomy and Behavior

Flies are like tiny, efficient machines. A housefly’s body splits into three parts: head, thorax, and abdomen. Their compound eyes, with thousands of tiny lenses, and lightning-fast nervous system work together to help them escape threats almost instantly, making them nearly impossible to catch. Those spindly legs are covered in hairs that act like taste buds, letting flies “taste” surfaces. Housefly biology also includes a proboscis, a straw-like mouthpart for slurping liquids or dissolving solids into a soupy meal.

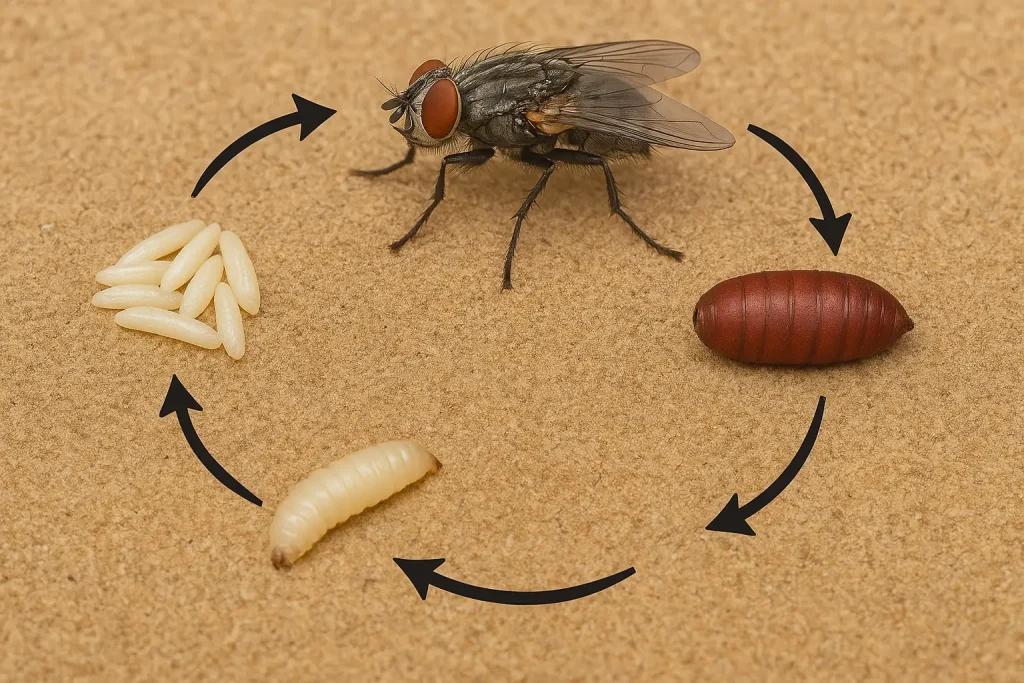

Flies are all about staying alive. Ever see a fly rub its legs together? It’s cleaning those sensory hairs to keep its senses sharp. Fly adaptations like these make them resilient, thriving in jungles, deserts, or city dumps. They’re also prolific breeders, with females laying hundreds of eggs in days, ensuring their populations rebound fast.

Flies are constantly searching for food, from decaying matter to sugary spills. Their ability to detect odors from miles away makes them nature’s cleanup crew, but also why they crash your picnic. Housefly biology equips them to survive almost anywhere, making them one of the most adaptable insects on the planet.

Ecological Importance

Flies might not be crowd favorites, but their fly ecosystem role is vital. They’re decomposers, breaking down dead plants, animals, and waste into nutrient-rich materials that enrich soil and support plant growth. Without flies, ecosystems would struggle to recycle organic matter efficiently. Housefly biology makes them perfect for this dirty work.

Bees get all the pollination glory, but some flies, like hoverflies, also spread pollen by visiting flowers, helping plants reproduce and keeping ecosystems diverse. Flies are also a key food source for birds, bats, spiders, and other insects. A world without flies would leave many predators hungry.

Flies contribute to research, too. Houseflies and fruit flies are studied for genetics, behavior, and disease transmission. Their short lifecycles and simple genomes make them ideal for experiments, leading to breakthroughs that benefit humans. While they can bug us, flies quietly keep ecosystems and science moving forward.

Flies aren’t perfect. They can spread bacteria by landing on contaminated surfaces and then your food. But even this negative role shows their influence—housefly biology makes them efficient carriers, for better or worse. Understanding their ecological contributions helps us see flies as more than just pests.

Evolutionary History

Flies have been around for about 250 million years, since the Permian period. Fossil records show early flies had longer wings or bulkier bodies. Over time, insect evolution shaped them into the sleek, agile creatures we know today, perfectly suited for a changing world.

Housefly biology as we know it took shape around 65 million years ago, during the rise of mammals and flowering plants. This era saw flies develop traits like compound eyes and specialized mouthparts. These fly adaptations let them exploit new food sources, from nectar to decaying matter, giving them an edge in diverse environments.

Flies share a common ancestor with butterflies and bees but took a unique evolutionary route. While bees became pollinator pros, flies leaned into scavenging and opportunism. This divergence shows how insect evolution can lead to wildly different outcomes, making flies a fascinating case study in adaptation.

Their ability to evolve quickly has kept flies thriving through mass extinctions and climate shifts. Housefly biology reflects millions of years of fine-tuning, ensuring they remain one of nature’s most resilient creatures.

Human Interactions

Flies and humans have a love-hate relationship—mostly hate. Housefly biology makes them pests, drawn to food, garbage, and even our sweat. They’ve been linked to diseases like cholera and dysentery, which is why we’ve spent centuries inventing traps, swatters, and sprays to keep them away.

Flies aren’t just troublemakers. Fruit flies, close cousins of houseflies, have driven major genetic discoveries, helping us understand heredity to cancer. Housefly biology even inspires technology—engineers study their flight for better drones. Their resilience makes them a model for innovation.

Our efforts to control flies have shaped their populations. Pesticides and sanitation have forced flies to adapt, sometimes becoming resistant to our defenses. This back-and-forth shows how deeply intertwined humans and flies are, and why understanding their biology matters.

Leave a Reply