Introduction

The history of technetium documents key developments in nuclear chemistry. As element 43, technetium is the lightest with all isotopes radioactive, synthesized in 1937. For example, it supports accurate kidney function tests in nuclear medicine. This article examines its prediction, discovery, technological advancements, and modern uses. Its radioactivity, however, requires careful management. The history of technetium traces advances in synthetic elements. Evidence from nuclear science underscores its role.

Technetium’s absence in stable forms challenged early researchers. Predicted by Dmitri Mendeleev, it was created artificially, marking a chemical milestone. Its applications span medicine and astrophysics. Historical data, therefore, clarify its significance. This analysis covers technetium’s scientific journey and challenges. The history of technetium reveals its impact on multiple fields.

Prediction and Early Claims

The history of technetium began with Dmitri Mendeleev’s periodic table. In the 1870s, he identified a gap at atomic number 43, naming the predicted element ekamanganese. Its expected properties resembled manganese and rhenium. For example, chemists analyzed molybdenite ores using spectroscopy to detect ekamanganese. Early searches failed due to technetium’s radioactive decay. Mendeleev’s prediction guided later efforts. This foresight shaped periodic table research.

Between 1828 and 1908, chemists reported finding element 43, suggesting names like polinium and nipponium. These claims, based on ore analysis, were disproved, as technetium lacks stable isotopes. Japanese chemist Masataka Ogawa’s 1908 nipponium, for instance, was likely rhenium. Such errors stemmed from limited detection methods. The discovery of technetium awaited nuclear technology. These early attempts highlight persistent scientific inquiry.

In 1925, Walter Noddack, Ida Tacke, and Otto Berg claimed element 43, naming it masurium. Their X-ray spectroscopy on columbite showed a weak signal, but Paul Kuroda’s 1989 study found technetium’s presence was negligible at 3 × 10⁻¹¹ μg/kg ore. Replication failures and political biases led to rejection. For example, post-war skepticism dismissed German claims. The history of technetium includes these disputed efforts. Advanced methods later confirmed its synthesis.

Discovery of Technetium

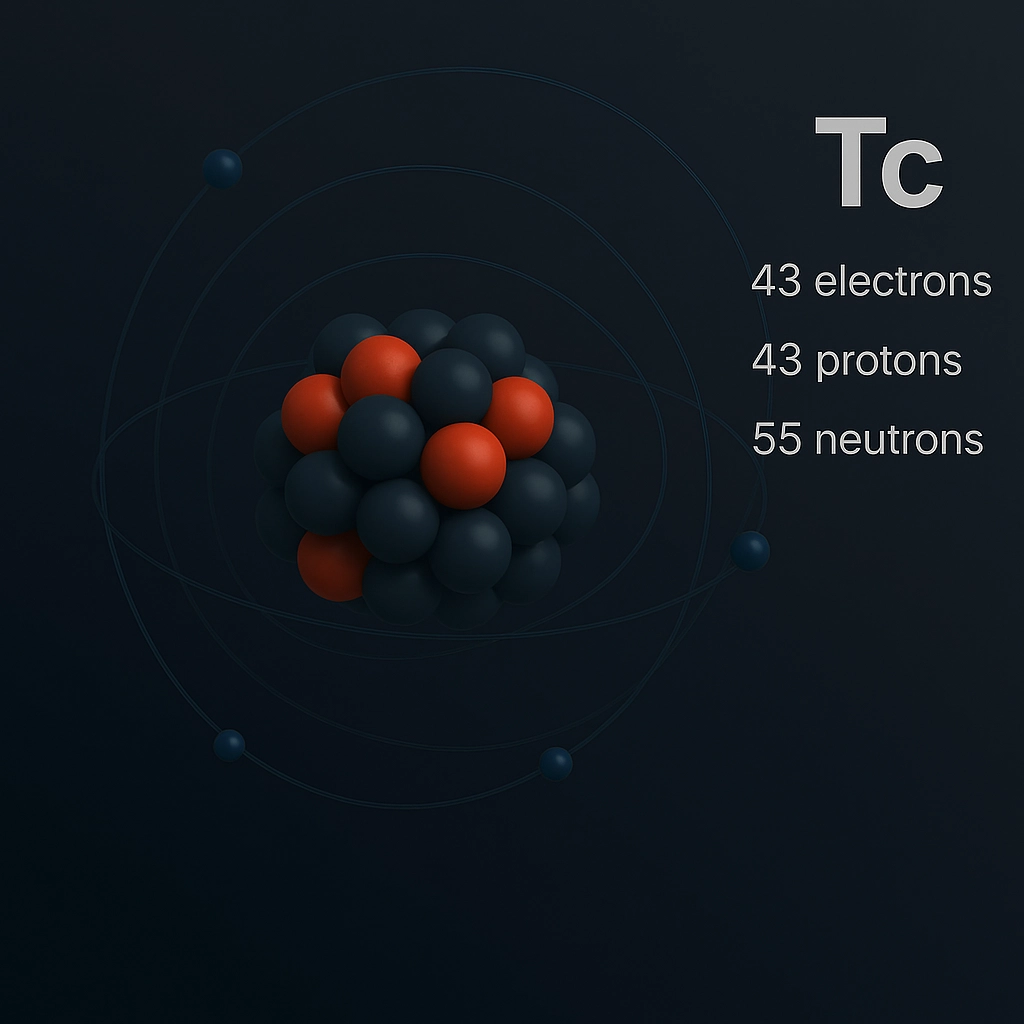

The discovery of technetium in 1937 marked a nuclear chemistry advance. Carlo Perrier and Emilio Segrè synthesized it at the University of Palermo, bombarding molybdenum with deuterons in a Berkeley cyclotron. They produced technetium-95m and technetium-97, confirming atomic number 43. For example, precipitation tests separated technetium from molybdenum and rhenium. The history of technetium centers on this synthesis. It was the first artificially created element. Cyclotron technology enabled this breakthrough.

Segrè sourced radioactive molybdenum foil from Ernest Lawrence’s cyclotron. With Perrier, he isolated isotopes with half-lives of 50–90 days, ruling out natural occurrence. Their analysis confirmed technetium’s unique properties. Handling its radioactivity, however, required precautions. The discovery of technetium validated Mendeleev’s periodic table. Its synthesis opened new research avenues. Nuclear methods redefined element identification.

The name technetium, from the Greek “technetos” (artificial), was chosen to reflect its synthetic nature. Palermo officials suggested “panormium,” but Perrier and Segrè preferred technetium, formalized in 1947. No primordial technetium persists due to its 4.2-million-year maximum half-life. For example, its instability explains its earthly rarity. The history of technetium highlights naming debates. This choice emphasized its laboratory origin.

Technological Advancements in Technetium Use

Technetium isotope production advanced significantly after its discovery. By the 1940s, nuclear reactors isolated technetium-99, a fission product with a 211,100-year half-life, in kilogram quantities. Its beta decay suited equipment calibration. For example, technetium-95m, with a 61-day half-life, improved nuclear detector accuracy. These methods scaled technetium’s availability. The history of technetium includes reactor-based production. Such advancements supported diverse applications.

Molybdenum-technetium generators, developed in the 1960s, enabled medical isotope production. These devices isolate technetium-99m from molybdenum-99 decay, providing a short-lived isotope for diagnostics. Hospitals use generators to supply technetium-99m for renal scintigraphy, assessing kidney function. For instance, its gamma emissions enable clear imaging in renal scintigraphy. Technological advancements in technetium transformed nuclear medicine. Supply chain issues, however, disrupt availability. Generators remain critical for healthcare.

Imaging technology enhanced technetium’s medical applications. Since the 1970s, gamma cameras have detected technetium-99m’s emissions, supporting bone scans for cancer detection. Chemical binding to molecules targets specific tissues, like skeletal structures. Safety protocols manage its radioactivity effectively. For example, low doses minimize patient risk. Technetium isotopes lead in diagnostic precision. Yet, reliance on reactor-produced molybdenum-99 poses challenges. These advancements drive medical innovation.

Production challenges include nuclear waste and supply constraints. Technetium-99 accumulates in reactor waste, requiring secure containment. Reactor shutdowns in the 2010s caused technetium-99m shortages, impacting diagnostics. Environmental releases, like 0.75 TBq from Chernobyl, show technetium’s mobility as TcO₄⁻ in water. For instance, waste immobilization remains unresolved. The history of technetium balances technological gains with risks. Sustainable production methods are under development.

Modern Applications and Challenges

Technetium-99m supports millions of medical procedures annually. Its gamma emissions enable imaging for bone scans, kidney tests, and cancer detection. Bound to radiopharmaceuticals, it targets tissues with precision. For example, renal scintigraphy measures kidney filtration with high accuracy. Its medical dominance stems from minimal patient exposure. However, aging reactors limit technetium-99m production. The history of technetium underscores its diagnostic importance.

Technetium has industrial applications, such as corrosion inhibition. The pertechnetate ion (TcO₄⁻) protects steel in boiler systems at 55 ppm, preventing rust. Technetium-95m calibrates nuclear equipment, leveraging its 61-day half-life. Its superconductivity below 11 K aids MRI magnet research. For instance, these uses exploit technetium’s unique properties. Radioactivity, however, restricts broader adoption. Technetium’s industrial roles remain specialized.

In 1952, Paul Merrill identified technetium’s spectral lines (e.g., 403.1 nm) in red giants and asymptotic giant branch stars. This confirmed stellar nucleosynthesis, showing heavy element formation. Technetium’s 4.2-million-year half-life suits aging stars. For example, its presence informs models of stellar evolution. The history of technetium extends to astrophysics. Its stellar detection contrasts with terrestrial absence.

Environmental challenges arise from technetium’s radioactivity. Technetium-99, a fission byproduct, contaminates nuclear sites, with TcO₄⁻ threatening groundwater. Medical waste from technetium-99m requires secure disposal. Regulatory limits, for instance, curb industrial use due to toxicity. Developing non-reactor production, like cyclotron-based methods, addresses supply issues. The history of technetium reflects application and caution. Managing waste ensures its safe use.

Leave a Reply