Introduction

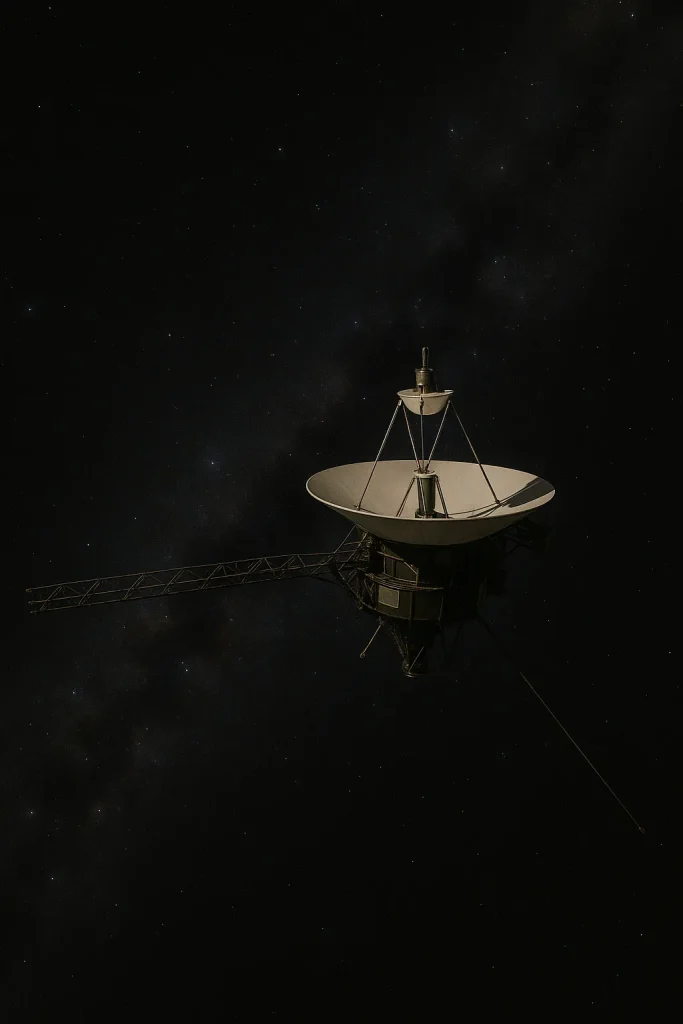

The Voyager mission stands as one of humanity’s most ambitious space explorations. Launched by NASA, it aimed to study the outer planets. Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, twin spacecraft, embarked on this journey in 1977. By May 2025, both probes are in interstellar space. This article explores their purpose, achievements, and current status. It covers their scientific tasks, historical significance, and lasting legacy. The Voyager mission continues to captivate scientists and the public alike.

The program took advantage of a rare planetary alignment. This alignment allowed the spacecraft to visit multiple planets efficiently. Each probe carries a Golden Record, a message for potential extraterrestrial life. The mission’s discoveries reshaped our understanding of the solar system. It also marked a milestone in space exploration history. Transitioning to origins, the next section delves into the mission’s beginnings.

Origins and Launch of the Voyager Mission

The Voyager mission originated in the 1960s, inspired by a rare cosmic event. Every 176 years, the outer planets—Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune—align on one side of the Sun. NASA saw an opportunity to explore these worlds using gravity assists, a technique that slingshots spacecraft to save fuel. Initially called the Grand Tour, the plan was scaled back due to budget constraints. The renamed Voyager mission focused on Jupiter and Saturn. It kept options open for extended exploration.

Voyager 2 launched first on August 20, 1977, from Cape Canaveral, Florida. It used a Titan-Centaur rocket for its journey. Voyager 1 followed on September 5, 1977, on a faster trajectory. Despite launching later, Voyager 1 reached Jupiter first due to its optimized path. The mission aimed to study planetary atmospheres, rings, and moons. It also set the stage for groundbreaking discoveries.

The spacecraft were designed for a five-year lifespan initially. Engineers equipped them with radioisotope thermoelectric generators, which convert heat from plutonium-238 decay into electricity, ensuring power far from the Sun. This design allowed the probes to operate for decades. The mission’s foundation blended innovation with ambition. The next section examines their planetary flybys.

Planetary Flybys and Scientific Discoveries

The Voyager mission began with detailed studies of Jupiter and Saturn, revealing unprecedented insights into these gas giants. Voyager 1 reached Jupiter on March 5, 1979, capturing high-resolution images of its turbulent atmosphere, dominated by the Great Red Spot—a storm larger than Earth. It discovered a faint ring system around Jupiter and identified two new moons, Thebe and Metis, expanding our catalog of the planet’s satellites. The spacecraft’s most striking find was active volcanism on Io, a moon with sulfur-driven eruptions, the first evidence of such activity beyond Earth. Voyager 1’s flyby of Saturn in November 1980 revealed five new moons and intricate ring structures. Its trajectory focused on Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, where it measured a thick, nitrogen-rich atmosphere denser than Earth’s, suggesting complex organic chemistry.

Voyager 2 followed a broader path, visiting Jupiter in July 1979 and Saturn in August 1981, confirming many of Voyager 1’s findings while adding new data. Its mission extended to Uranus and Neptune, a historic first for any spacecraft. At Uranus in January 1986, Voyager 2 discovered 10 new moons and two additional rings, while also measuring the planet’s magnetic field, which was unexpectedly tilted 59 degrees from its rotational axis—a puzzle for planetary scientists. In August 1989, Voyager 2 reached Neptune, capturing 10,000 images of its dynamic, deep-blue atmosphere, driven by winds up to 1,500 mph. It identified faint rings and a massive storm called the Great Dark Spot, alongside six new moons, enriching our understanding of this distant world.

Both spacecraft analyzed magnetic fields, revealing how they interact with solar wind across vast distances. They also studied atmospheric compositions, finding helium and hydrogen dominate these gas giants, with trace methane giving Uranus and Neptune their blue hues. The data from these flybys remain a cornerstone of planetary science, informing models of planetary formation. Voyager 2’s extended journey provided a comprehensive view of the solar system’s outer reaches. The next section explores their transition to interstellar space.

Transition to Interstellar Space

After completing their planetary flybys, the Voyager mission entered a new phase with the Voyager Interstellar Mission in 1990. The goal was to explore beyond the heliosphere—the Sun’s protective bubble of magnetic fields and solar wind. Voyager 1 crossed the heliopause, the boundary where solar wind meets interstellar medium, on August 25, 2012, at 122 AU (1 AU = distance from Earth to Sun). It became the first human-made object to enter interstellar space, a historic milestone. Voyager 2 followed on November 5, 2018, at 119 AU, confirming the transition with its working plasma science instrument.

In interstellar space, the probes measure cosmic rays, plasma waves, and magnetic fields, providing unprecedented data on this uncharted region. Voyager 1, despite a failed plasma science instrument since 1980, used its plasma wave subsystem to detect oscillations indicative of interstellar plasma—denser than inside the heliosphere at 0.08 particles per cubic centimeter. Voyager 2’s plasma instrument directly measured a sharp drop in solar wind speed, from 300 km/s to near zero, alongside a rise in cosmic ray intensity, confirming its exit. Magnetic field data from both probes revealed a shift in orientation, aligning with the galactic field rather than the Sun’s, with Voyager 2 noting a 20-degree shift in field direction. These measurements help scientists understand the heliosphere’s shape, now believed to be comet-like with a rounded nose and trailing tail.

Communication with the probes continues via NASA’s Deep Space Network, though signals take over 22 hours to travel from Voyager 1 to Earth. Power management is critical as their generators degrade at 4 watts per year; by 2025, some instruments have been powered off to conserve energy. The spacecraft face challenges like aging thrusters, yet engineers extend their lifespans through careful resource allocation. The Voyager mission now explores the boundary between our solar system and the galaxy. The next section discusses the Golden Record’s role in this journey.

The Golden Record: A Message to the Cosmos

Each Voyager spacecraft carries a Golden Record, a 12-inch gold-plated disc intended as a message for potential extraterrestrial civilizations. Curated by a team led by Carl Sagan, the record contains 115 images, 90 minutes of music, and natural sounds like whales, thunder, and human laughter. It includes greetings in 55 languages, from ancient Akkadian to modern English, alongside messages from global leaders, such as then-UN Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim. The record aims to represent humanity’s diversity and creativity. It serves as a cosmic time capsule, preserving Earth’s essence. If discovered, it could introduce humanity to another intelligence.

The Golden Record’s cover features instructions for playback, etched with symbols showing Earth’s location relative to 14 pulsars for navigation. Plated with uranium-238, its half-life of 4.5 billion years allows future finders to date the record through radioactive decay. The Voyager mission thus extends beyond scientific discovery, carrying a cultural legacy into the cosmos. The record reflects optimism about intelligent life elsewhere, a gesture of connection across unimaginable distances. While no contact has been made, its symbolic value endures. The final section assesses the mission’s current status and impact.

Leave a Reply