Introduction

Imagine a single grain that sparked the rise of empires and fed the world for millennia. Wheat (Triticum spp.), one of humanity’s greatest agricultural triumphs, did just that. First cultivated around 10,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent, this humble cereal grain transformed societies by enabling settled agriculture, spurring population growth, and paving the way for cultural and economic progress. Today, wheat is a global powerhouse, grown everywhere except Antarctica, with annual production surpassing 700 million metric tons. Its versatility powers an array of foods—bread, pasta, noodles, cakes, and cereals—while its by-products fuel industries and livestock. Rich in carbohydrates, proteins, vitamins, and minerals, wheat bolsters global food security. It supports millions of farmers economically and weaves itself into the cultural tapestry of cuisines worldwide, symbolizing sustenance and tradition. This article delves into wheat’s remarkable history, its vital importance, its cultivation, and its diverse uses, concluding with a look at its future amid a changing world.

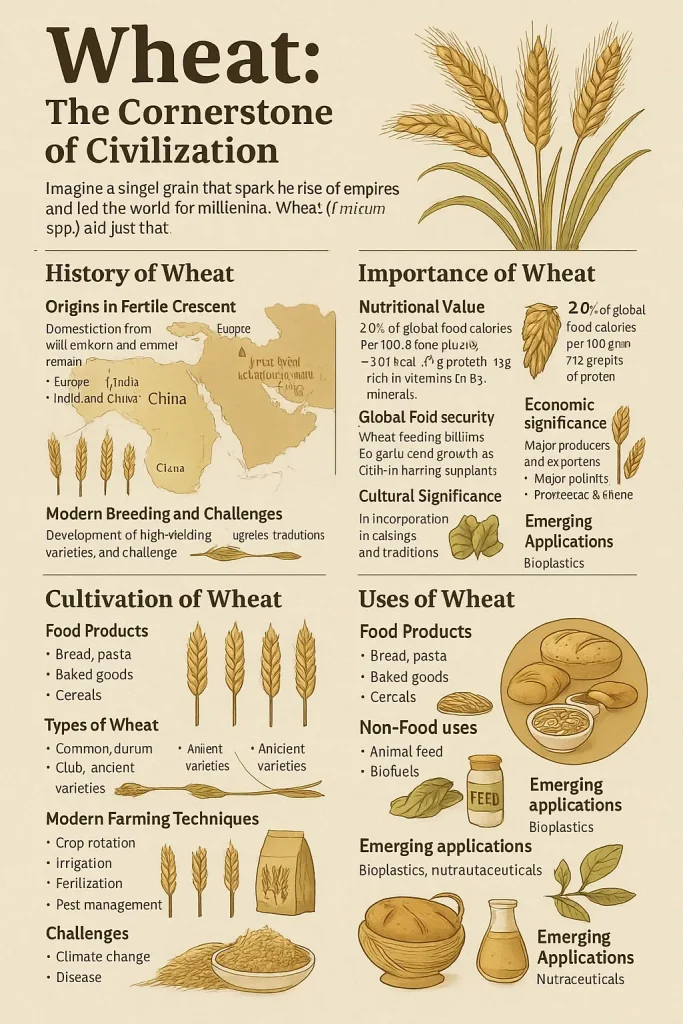

History of Wheat

Origins in the Fertile Crescent

spanning modern-day Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, and parts of Turkey and Iran. Archaeological evidence pinpoints its cultivation to around 9600 BC, though hunter-gatherers harvested wild wheats as early as 21,000 BC. Early species like wild einkorn (T. monococcum subsp. boeoticum) and emmer (T. turgidum subsp. dicoccoides), from the Triticeae family, enticed humans with their tasty, nutrient-packed seeds.

Domestication unfolded slowly. Early farmers favored plants with larger grains and non-shattering heads—traits that tied the crop’s survival to human hands. Einkorn took root in Southeast Anatolia by 8800 BC, evidenced at sites like Çayönü and Cafer Höyük. Emmer emerged in the southern Levant around 9600 BC, with firm proof from Çayönü between 8300–7600 BC. Genetic studies reveal multiple domestication events, showcasing this ancient cereal’s remarkable adaptability.

Spread Across Continents

Wheat’s domestication shifted humanity from roaming hunter-gatherers to rooted farmers. By 8600 BC, emmer reached Cyprus, with einkorn following by 7500 BC. It spread to Greece by 6500 BC, Egypt by 6000 BC, and Germany and Spain by 5000 BC. By 4000 BC, it graced the British Isles and Scandinavia, hitting India by 3500 BC and China’s lower Yellow River by 2600 BC.

Trade, migration, and wheat’s climate flexibility drove this expansion. Neolithic farmers (8500–4000 BC) wielded stone-bladed sickles to harvest it efficiently. After 8500 BC, wheat thrived in grasslands and wetlands via décrue farming, a low-effort technique using seasonal floods.

Impact on Civilization

Wheat fueled the rise of civilizations. Its steady supply supported population booms and permanent settlements. At Çatalhöyük (7100–6000 BC), wheat became bread, porridge, and gruel, while its straw served as fuel, wicker, and building material. Hexaploid wheat, emerging around 6400–6200 BC at Çatalhöyük, birthed yeasted breads—a culinary leap.

By the 12th century, the UK milled wheat into flour widely. By the 19th century, it was the nation’s top crop for human consumption. The Industrial Revolution mechanized farming and milling, boosting output. The 20th-century Green Revolution introduced dwarf varieties, skyrocketing yields but shrinking genetic diversity as landraces faded.

Modern Breeding and Challenges

Wheat breeding kicked off in the 19th century, selecting single-line varieties for key traits. The 20th century tied it to Mendelian genetics, crossing lines for inbred cultivars. Today, common wheat (T. aestivum) dominates with 95% of production, while durum wheat (T. durum) holds 5%. Yet, losing landraces—diverse, farmer-bred strains—heightens risks from pests and climate shifts.

Wheat’s history mirrors its vast influence, from sparking agriculture to molding economies and cultures. Its evolution through breeding keeps it vital, though new challenges demand fresh solutions.

Importance of Wheat

Nutritional Value

Wheat powers 20% of global food calories. Per 100 grams of raw red winter wheat, it delivers 327 kcal, 71.18g carbohydrates, 12.61g protein (13% gluten), 1.54g fat, and 12.2g fiber. It’s packed with vitamins—thiamine (32% DV), niacin (34% DV), B6 (18% DV)—and minerals like iron (18% DV), magnesium (30% DV), zinc (24% DV), and manganese (173% DV).

Though rich in plant protein, wheat lacks sufficient lysine per WHO standards. As a whole grain, its fiber benefits all ages.

Global Food Security

Wheat feeds billions, a staple from Europe to Asia. Its affordability, high yield, and storability combat hunger, especially in developing nations. The Green Revolution, boosting India’s output, curbed famines and steadied food supplies.

Economic Significance

Wheat’s a trade titan, worth billions yearly. Top producers—China, India, Russia, the U.S., and France—feed global demand, while exporters like the U.S., Canada, and Australia dominate markets. In India’s Punjab, it’s a farmer’s lifeline. Price swings ripple worldwide, affecting food costs.

Cultural Significance

Wheat’s cultural roots run deep. Italy’s pasta relies on durum, India’s roti on bread wheat, and the Middle East’s pita on local strains. Festivals and rites, like the Christian Eucharist, honor wheat as abundance incarnate.

Beyond nutrition, wheat shapes economies, cultures, and food systems. Its cultivation is key to global stability.

Cultivation of Wheat

Climate and Soil Requirements

Wheat adapts to temperate and subtropical zones, thriving with 250–1,300 mm rainfall and 3°C–30°C temperatures. It prefers well-drained, fertile soils (pH 6.0–7.2). Loamy, organic-rich soils excel, but wheat manages poorer ones with care.

Types of Wheat

Cereal varieties suit distinct needs:

Common Wheat (T. aestivum): Bread, pastries, all‑purpose flour; 95 % of global output.

Protein‑rich Durum grain (T. durum): Ideal for pasta and semolina; big in Mediterranean areas.

Soft‑kernel Club variety (T. compactum): Perfect for cakes and crackers.

Spelt heritage grain (T. spelta): Ancient, for specialty breads.

Einkorn and Emmer: Niche ancient grains.

In India, T. aestivum rules the north, while T. durum dominates the center and west.

Modern Farming Techniques

Today’s methods boost yields:

Crop Rotation: Improves soil, cuts pests.

Irrigation: Vital in dry zones like India.

Fertilization: Uses nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and now sulphur.

Pest Management: Tackles aphids, rusts, weeds holistically.

Mechanized Harvesting: Combines slash labor costs.

Challenges

Wheat faces hurdles:

Climate Change: Droughts, floods, heat hit yields.

Pests and Diseases: Rusts, smuts, Hessian flies loom.

Sustainability: Chemical overuse degrades soil, water.

Genetic Diversity: Landrace loss risks resilience.

Research targets tougher varieties and precision farming to keep wheat thriving.

Uses of Wheat

Food Products

Wheat’s flour anchors countless foods:

Bread: High-gluten bread wheat for loaves, pizza.

Pasta: Durum’s protein shines in spaghetti, couscous.

Baked Goods: Soft wheat for cakes, cookies.

Cereals: Processed into bran flakes, shredded wheat.

19th-century milling refined white flour, boosting shelf life and scale.

Non-Food Uses

By-products shine too:

Animal Feed: Bran, middlings for livestock.

Biofuels: Grain, straw for ethanol.

Industrial Products: Starch in adhesives, textiles; gluten in meat substitutes.

Straw: Bedding, fodder, construction.

Emerging Applications

New uses emerge: wheat-based bioplastics and bio-composites offer green alternatives. Its fiber and nutrients spark nutraceutical interest.

Wheat’s range spans food, farming, and industry, adapting to mdern needs.

Conclusion

From a wild grass in the Fertile Crescent to a global staple, wheat’s tale is one of ingenuity and resilience. Its domestication birthed agriculture, fueling civilizations and shaping history. Now, it nourishes billions, props up economies, and colors cultures. Yet, climate change, pests, and sustainability test its future. Research into hardy strains, smart farming, and green uses lights the path forward. With a growing world to feed, wheat’s role in food security and stability is non-negotiable. Through innovation and care, wheat can remain humanity’s cornerstone for generations to come.

External References on Wheat

- For a scientific overview of wheat’s role in global agriculture and food systems, refer to the FAO’s official publication: Wheat: The Most Widely Grown Crop in the World – Published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

- For historical and economic insights into wheat’s global importance, see this article by the Smithsonian Magazine: How Wheat Made Us Modern – A scholarly yet accessible resource on the cultural and economic evolution of wheat.

Leave a Reply