Introduction

The wound healing process restores skin integrity after injury. When cuts or burns breach the skin, the body triggers repair through inflammation and tissue regrowth. For instance, a shallow scrape heals within days, forming fresh skin. This article explores why wounds occur, how they recover, and why some persist. Chronic wounds, however, challenge medical systems. The wound healing process documents biological repair. Scientific insights drive effective treatments.

Despite disruptions, the body’s repair mechanisms excel. From clotting to scar formation, coordinated cellular steps mend tissue. Meanwhile, modern therapies enhance outcomes, though chronic cases resist healing. Consequently, historical data illuminate repair pathways. This analysis traces healing stages and barriers. The science of healing fuels medical advancements.

Causes of Wound Formation

Wounds form when skin’s protective barrier breaks. Physical trauma, such as lacerations or abrasions, causes bleeding and exposes deeper tissues. A knife cut, for example, damages both epidermis and dermis. Swiftly, inflammation activates to shield the site. The causes of wound formation stem from external injuries. Such damage initiates the wound healing process. Tissue disruption prompts immediate repair.

Within hours, inflammation combats potential infections. Neutrophils and macrophages clear bacteria, guided by cytokines signaling immune response. Swelling, for instance, reflects active defense mechanisms. Yet, excessive inflammation can hinder recovery. The causes of wound formation include this immune surge. In contrast, balanced inflammation aids healing. This response shapes subsequent repair stages.

Certain conditions amplify wound severity. Poor circulation, often from peripheral artery disease, restricts oxygen to tissues. Repeated pressure, like in bedridden patients, leads to ulcers, with 60% occurring in hospitalized elderly. Thus, systemic factors complicate repair. The causes of wound formation highlight vulnerabilities. For example, chronic conditions delay recovery. Risk factors dictate healing challenges.

The Wound Healing Process

The wound healing process unfolds across four distinct stages. Immediately, hemostasis halts bleeding as platelets form clots and vessels constrict. Within minutes, for example, a clot seals a minor cut. This rapid response prevents blood loss. Consequently, clotting lays the foundation for repair. The body’s efficiency is remarkable. Hemostasis ensures swift protection.

Next, inflammation clears threats, peaking within 1–3 days. Neutrophils eliminate bacteria, while macrophages remove debris, with cytokines driving redness and warmth. Pus, for instance, signals infection control. The wound healing process hinges on this stage. However, prolonged inflammation stalls progress. In contrast, controlled inflammation supports recovery. This balance is critical for healing.

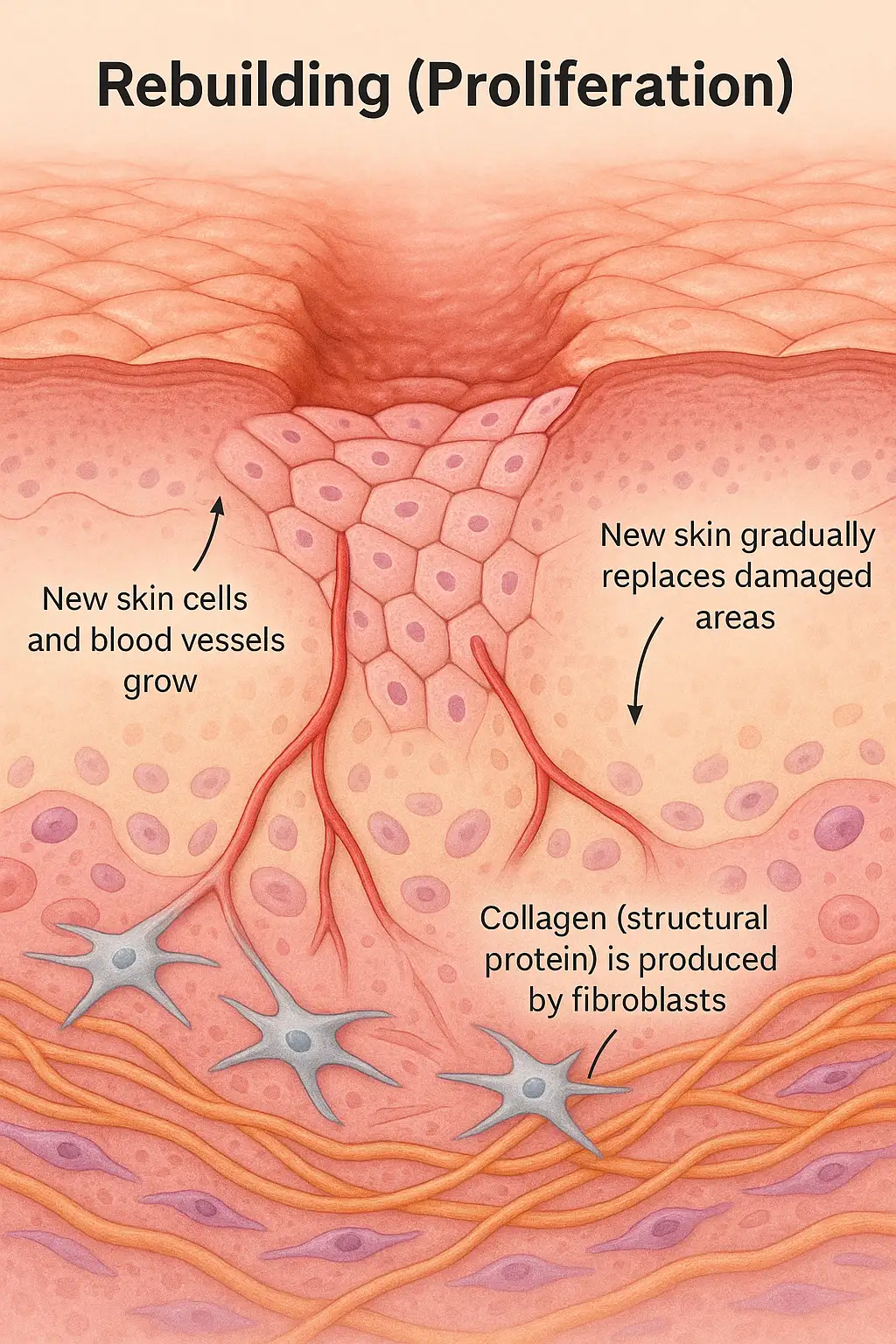

Over days to weeks, proliferation rebuilds tissue. Fibroblasts weave collagen, and new blood vessels supply nutrients, forming granulation tissue. A deep wound, for example, develops pink tissue during repair. Thus, proliferation restores skin structure. This phase drives visible recovery. Notably, the body excels at tissue regeneration. New skin forms a robust scaffold.

Finally, remodeling strengthens scars over months. Collagen fibers reorganize, enhancing durability, though scars remain less flexible. A year-old scar, for instance, gains strength but stays visible. Remodeling refines tissue integrity. Consequently, the process concludes with functional skin. Long-term repair ensures lasting protection. The body’s precision shapes outcomes.

Advancements in Wound Care

Modern advancements enhance the wound healing process. Bioengineered dressings, like hydrocolloids, maintain moisture, speeding proliferation by 20% compared to traditional gauze, which dries wounds and delays repair. Since the 1980s, these dressings have lowered infection rates. For example, they protect burns effectively. Yet, their high cost limits access. The advancements in wound care improve outcomes. Technology transforms treatment efficacy.

Growth factor therapies accelerate repair, unlike inconsistent traditional salves. Platelet-derived growth factors, applied as gels, boost collagen, healing diabetic ulcers 30% faster. Becaplermin gel, for instance, targets chronic wounds. Clinical trials confirm its efficacy. However, costs restrict widespread use. In contrast, salves offer affordability but limited results. These therapies mark significant progress in wound management.

Stem cell treatments regenerate tissue, surpassing manual debridement’s variable outcomes. Mesenchymal stem cells promote angiogenesis, improving closure rates by 40%. Since 2010, they’ve aided burn recovery. For example, stem cells reduce scarring. Debridement, though, is labor-intensive and less precise. Nevertheless, regulatory barriers slow stem cell adoption. Emerging therapies promise better chronic wound healing.

AI diagnostics outpace traditional clinical judgment, which achieves ~60% accuracy. AI algorithms, trained since 2015, predict healing with 85% accuracy, guiding precise plans. For instance, AI detects early infections. Unlike subjective assessments, AI offers consistency, though data privacy raises concerns. These tools redefine wound care. Advancements in wound care leverage cutting-edge technology. Precision drives future treatments.

Challenges in Chronic Wound Healing

Chronic wound healing falters under systemic conditions. Diabetes, affecting 30% of chronic wound patients, impairs circulation and immune response. Elevated glucose slows collagen, prolonging proliferation. Diabetic foot ulcers, for example, persist for months. These wounds resist standard care. Consequently, systemic diseases disrupt repair. Holistic management becomes essential.

Infections, affecting 15% of chronic wounds, hinder recovery. Bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus form biofilms, resisting antibiotics and stalling inflammation. Infected ulcers, for instance, require debridement. Infections exacerbate chronic wound healing barriers. Aggressive interventions, such as antimicrobial dressings, are needed. In contrast, early detection improves outcomes. Microbial resistance complicates treatment.

Poor nutrition and inadequate care stall repair. Zinc and vitamin C deficiencies weaken collagen, while irregular dressing changes raise infection risks. Malnourished patients, for example, heal slower. These factors obstruct the wound healing process. Comprehensive care, including diet, is critical. Nevertheless, resource limitations challenge management. Addressing barriers enhances recovery prospects.

Leave a Reply